WRITERS TELL ALL

|

Matthew Turbeville: You’ve written so many books, and they are, frankly, amazing. What do you think the purpose of writing really is? If you had to leave everything to one answer, what answer would you give to the question: “Why should someone write?”

Marcus Sedgwick: Well, I can see from your question that you know there are far too many responses to the matter of what writing is all about, so you’ve limited me to one answer. This is a low, underhand trick, so let me pull a low-down dirty trick in reply. To ‘Why should someone write?’ I would say ‘Why shouldn’t they?’ But now I look at that reply, although I have side-stepped answering your question, I think the possible answers to my reply might be able to tell us something. Although it was meant rhetorically, if you were to answer ‘why shouldn’t they write?’ with an actual answer, we could learn something from that answer. For example, if we said, ‘because you’re not good enough’, we might wonder, ‘oh yeah? Who says? And what do you define as good anyway?’ Or if we replied, ‘because you can’t make money out of being a writer’, we can wonder if we have a good motivation to try to be a writer in the first place. Or if we replied ‘Because all the good books have already been written’, we might release that every writer since writers weren’t writers but oral storytellers has probably had the same worry. And yet done it anyway. All these answers expose our fears and worries about what writing can’t be, or isn’t, and so their reverse therefore tells, frees us, to actually try. MT: Your book deals a lot with time, and I’ve been thinking about some of my favorites of yours, and also Proust, now that I’ve reached a period in my life where I’m experiencing tremendous loss. How do you incorporate ideas of time, and being, into these great work for the youth of the world? MS: It’s not something I consciously do for the most part. I think this is true of lots of aspects of writing, in that the stuff that really ‘means’ something to people comes along for the ride. It hitchhikes on the back of the story. The most important thing is to tell a good story (and we can argue for days over what that might be) and then, if you have done that well, you get the chance for people to read some thoughts about Being and Time, and now I sound like Heidegger. So for the most part, I trust that these things will emerge naturally from the story, though I might on occasion deliberately pull at one cord here, or push one lever there, in order to emphasize some existential thing like time. I’m talking about on the level of an individual sentence or short paragraph perhaps. That can be fun, but you mustn’t get carried away, because the story must always come first. Finally, I trust that notions of being and time willemerge naturally since I have felt a strong connection, awareness to these things since childhood; I have always questioned my/the sense of time (for example, with my own age, even when I was tiny I also felt very old) and since they are deep preoccupations, you cannot help but that they will emerge spontaneously in a book. MT: Your books never belittle young people. You write amazingly, with style and plotting that’s sharp and near perfect. Why do you think it’s important not to somehow change books to fit into a young adult or child’s world? Do you think children and young adults are often underestimated, or what are your reasons for writing the way you do? What audience do you believe you are writing for? MS: To take those questions in reverse order. Like many writers I know and have heard, I am not writing for any audience other than myself, and maybe simultaneously some detached observer version of myself, who might be me in other people, at a variety of ages. But basically I write to please myself, to scratch whatever itch is in the depths of the mind. Now, I am always saying that writing contains many, many contradictions, and here’s one of them, because it is possible to write simultaneously only for oneself, and yet still have thoughts about readers too. But if the White Queen can believe in six impossible things before breakfast, so can we. That’s why we’re people and not computers, we can run two pieces of conflicting software at the same time, and contradictions, even apparently mutually exclusive ones, are all part of what people are and therefore what writers are. (It’s why a computer won’t ever write a good book. I hope.) I fully believe that we constantly underestimate children and teenagers and it mystifies me why we do. I mean, how many years really is it since we were children? Is it really so hard to remember that time when you heard something, felt something, read something that people thought you didn’t understand but you did? Why are we so quick to put childhood behind us? Or try to, because, you basically can’t. Is everyone so arrogant as to think, well, I remember being a kid and everyone thought I was dumb and they were talking in front of me like I wasn’t there but I knew what was going on, but that no one else had that experience? I can remember being pre-verbal and having a tantrum because I couldn’t explain to my mother what was wrong and what I really wanted, and she was talking back to me like I was a toddler. Because I was. I didn’t even have the words, but I knew, my thoughts were wordless, but clear. And so I always talk to teenagers, children and eve babies as if they are adults. (I even talk to adultsas if they are adults though I am not sure I’ve met many in my life.) We constantly underestimate young people for what they can understand, what they want to deal with, what they can deal with, what they are ‘ready for’ (another thing which drives me insane) and so on. All I have tried to do in my books is be true to my belief about that. I know it might sound arrogant at first sight to say writing is for me, and not for anyone else; but it isn’t arrogant. It might be selfish(and there’s another contradiction of writing – it is the most self-ishthing I can think of, and yet, if done well, it can be shared and mean enormous amounts to many other people). But what would be more arrogant would be to say, okay, I’m a 52-year-old Briton, what would a 13-year-old girl in Brazil want to read? Or a 16-year-old boy in Berlin..? And then assume you know and actually be arrogant enough to ‘write them a book’. Finally, why all this is important is because if you don’t do these things, and if you treat your readers like idiots, then you will have an idiotic book. MT: Short stories are a major weakness for me. I love reading them but am terrible with writing them. Many of your books aren’t literal collections, but are novels that contain something like stories, these complete visions of people and places and actions that bleed into others. What do you think the trick is to writing a great short story, and why do you write books like the ones I described earlier, the bleeding kind? MS: I like the sound of bleeding books, in that that’s what a good book does, and what you aim for, something that forces or seeps or crawls or steals into someone’s (sub) consciousness and makes them feel and think things they weren’t expecting. If some of my books bleed in a different way – within themselves - I’m thinking Midwinterbloodor The Ghosts of Heaven, it’s because I wanted to give somewhat separate stories a unified power. I’m not sure I can say what the secret to writing great short stories is, but I do know this: whenever I have an idea for a story, I send some time looking at it, and one of the questions I ask myself is what kind of story would serve this idea best. Should it be a novel, or maybe it would be better as a radio play? Since I don’t write radio plays, I would then abandon it. Maybe it ought to be a film, or maybe the idea would be best served, given its best expression, as a short story, in which case I would put it away in a drawer for that increasingly rare day when someone invites you to write a short story. My wife just read a novel, I won’t say what, that wasn’t great, and at the end she concluded it might have been better off as a short story. So I know I’m not alone in this. MT: What excites you most about writing a book? Have you ever disposed of a book, falling out of love with it or not wanting to write it? Have you ever come back to a book you thought you were done with? MS: You never quite know what’s going to be exciting about a book, that in itself is one of the most exciting things about it. I don’t think I can give a short answer to that question apart from that. I have abandoned books, yes, often 10,000 words in (it’s pretty easy to put out 10,000 words without knowing what you’re doing) and a couple of times I’ve written whole books and thrown them away. That is not fun, and I try to avoid it happening. With my first ‘adult’ novel, which I wrote without contract in between other things, I wrote about half, then didn’t know whether it was worthwhile. And I had other things to do for six months or more, so I left it alone. When I came back to it I found it to be good enough for me to continue to the end. MT: What is your dream book? Has it been written by someone else, have you written it, or is it still to be written, perhaps by you? MS: I have several dream books; the one that means the most to me is The Magic Mountainby Thomas Mann, sadly not as widely read as it used to be, which is a shame as it still has so very much to offer. As for me, I think one of the thing about being a writer, a thing that forces you on, is the idea that one day you will write your dream book. But you never do. Or maybe, if you did, you would stop writing thereafter. But the chimerical illusion of perfection attracts you and draws you in to have another try. MT: Who are your favorite writers living today (or perhaps deceased)? Children’s books, young adult books, new adult books, adult books, whatever—and any genre, please. I love how you mix so many genres and forms of writing, and wonder what authors you admire with new and different ways of writing. MS: I meant to meant to say that I really appreciate your cross-genre/age notions on this site. I hate that we categorize stuff, I know we kind of have to, and it’s human nature to do so, but it’s not how a writer thinks, well not how this writer wants to think. That being said, I don’t have many favorite writers who are still alive! One or two, like Susan Cooper, Max Porter, Alan Garner, S E Lister – I would read anything they wrote. But I have trouble with a lot of more recent fiction, and by this I mean anything after about 1935 or something of that nature. Last year, someone sent me the transcript of an interview between the great Alan Garner and Aidan Chambers, an interview that took place in the 70s. In it, Garner also states he doesn’t like modern fiction for the reason that it has forgotten to say something important to the reader. It has, he says, forgotten to say ‘I love you’ to the reader. I am very touched and fascinated by this viewpoint and I guess, by extension that my problem with much modern fiction is that not only has it forgotten to say I love you but is instead saying ‘look how clever I am’. So my favorite writers at the moment are long dead: Artur Schnitzler, Adalbert Stifter, Willa Cather, Daphne Du Maurier, David Jones and of course, my hero, Thomas Mann. The writings of all these people say ‘I love you’. (I’m guessing David Jones isn’t so well known in the US? His book In Parenthesis, is for me, the best thing ever written in the English language. Forget the fact it’s ‘about’ his experiences in the first world war; it’s simply about being a frail, very human, loving being.) Oh, and I must mention my new love; a fantastic book called The World of Henry Orient. It was the debut novel by Nora Johnson, and it was published 64 years ago. Were it to be published today it would be published as a YA book, I feel sure, but at the time, since that category didn’t exist, it was an adult novel. This is why I hate classifications. It’s also one of the few reasons I am happy to be 52 years old, because the YA thing didn’t exist when I was its target demographic, and I firmly believe that the YA concept inhibits as many readers as it liberates. Anyway, to return to The World of Henry Orient. It is a sublime book, and wereit to be published today (which it practically could be, without a word changed) as a YA book, it would blow most of that field out of the water. It’s a small masterpiece, and yet again, it makes me wish we could dispense with categories for books, and just sort them into ‘good ones’ and ‘bad ones’, and then we could just spend our time arguing about what those terms might possibly mean. MT: You’re a literary superstar. I really do mean this—so many people are in awe of your books, of you, so much that you’re more than a person, even more than a legend. What responsibilities do you feel come with this, and do you ever feel there are parts of your life, or your writing, or your process that you have to keep to yourself? MS: I don’t mind sharing most of my thoughts, because, if we’re honest, they are to be found in my novels anyway. It’s all out there, so why hide it? But of course there are some things that are only for me, or my close family. Your words are very flattering but I am just someone who has enjoyed putting words together, sometimes it has been easy, sometimes hard, and along the way, you cannot help but learn stuff. A little about writing, a lot more about yourself. MT: Which book was hardest for you to write? Which book was your favorite? And which book are you most proud of, and why? MS: The books seem to be getting harder the longer I go on! I don’t want to sound like I am complaining, but really, most things get easier in life, the more you do them. Writing books is definitely getting harder. Some books have driven me crazy, because of plot, for example, She Is Not Invisible, which doesn’t appear to have a complex plot, but that’s because it’s all hidden underneath, invisible, in order for the ending to work. Mister Memorydoes have an on-the-surface complicated plot, and that took a lot of figuring out, over many years. Snowflake, AZwas hard to write because I had to put a lot more of myself in than usual, and I was scared. MT: Is there a genre or type of book you haven’t written, but feel you would love to write someday? MS: I have written lots of different things, and if there’s one thing I am proud of about my writing, it’s that if people know me at all, they probably know that every book is different. More or less. As I hinted at above, though, I don’t really like to think in terms of genre. I just like to write a book, and let publishers worry about what it is and where it goes. Having said thatthough, one thing that drives me on is the desire to write the ‘kind of book’ (whatever that is) that I haven’t yet written. With Snowflake, AZI wanted to write the sort of book where nothing much actually happens (apart from the end of the world quietly taking place in the background). I wanted the book to work because of the characters’ interactions, and not much more. And for the last few years, I have been wanting to write a funny book. I intended to before I wrote Saint Death, and then that story came along, and that’s the exact opposite of a funny book; it’s an angry book. But I keep hoping I will write a funny book, because I think genuinely funny books are very, very few, and that’s because they are very, very hard to write. If they were easy, there would be many more of them. I still would like to try, but we’ll have to see. MT: What do you hope your readers will take away from your books? Are there any of your books—because you’re quite prolific—which you like to think affect people most, and what do you hope readers take away from these books? MS: Oh golly, now that is a surprisingly hard question to answer. Maybe I am not the right person to answer that question, and yet I suppose no one else can answer it for me. Um. Let me just say that I get more letters about some books than others, and those books are Revolver, Midwinterbloodand The Ghosts of Heaven. I have had the nicest letters about that last book, ones that prove the point we were discussing above, that teenagers are perpetually underestimated by most of the adult world. I have letters that would make you cry with joy as a someone who promotes reading in young people, ones that would make you punch the air and say ‘yes! See what I mean?’ MT: You often write “linked stories,” and I wonder how you feel about the way people are connected in real life, since you write so often about, as described in relation to The Ghosts of Heaven, “the spiral of time.” How are we connected to the past, and what do you think, as with the nature of a book like Midwinterblood, we could and should learn from the past in order to move forward with the future? What’s so great about presenting a book like Midwinterblood to young people as well as adults? MS: Well, in the words of that famous quote by one of your countrymen, the past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past. It is very easy to each the conclusion that many if not all of the world’s problems are because we never fucking learn anything. Perhaps this is banal, but if so, it’s because it’s beyond cliché. People are forever being trapped by their past, the past of their families, the stories they told, the ones they didn’t tell, the words their family uses, their culture uses, their peers. And sitting inside everyone is that child they once were, who is also not dead, not even no-longer-a-child. So many people flee from their childhoods and maybe even more from teenage-hoods, and are doomed to fail because they never step out of the software that they have been running, that they were given by others, who were in turn given that programming by others. That’s why writers who do what I do are fascinated by the meaning of this time of life, and why it’s so challenging to work with, beyond what most people might imagine. MT: Some of your books contain parts that approach horror (and fantasy, too). What books scare you most, and what scares you most in real life? You write from so many genres, but are there any genres you wouldn’t venture into? MS: The books that scare me the most are 800 pages long and full of pretentious rubbish. As far as horror goes, I don’t tend to read horror so much these days. The creepiest thing I read in recent years would be Fever Dreamby Samanta Schweblin. That’s a good book. And it’s even modern. What scares me most in real life? That would be almost anything. I have been filling myself with real life horror for years, and I am coming to a few conclusions. One, in general, people don’t want to know about real life horror, it’s just too much. (Recently I had a professor of Societal Collapse write to me, after reading Snowflake, AZ - we got chatting over email and he ended up telling me how hard he is finding lockdown, mentally speaking. And he studies this kind of scenarios for a living!) Two, it’s extremely damaging to your physical and mental health to fill your head with the evils of Monsanto, or Bayer, or Unilever, or Nestlé, or the Koch brothers, or Facebook, or YouTube, or ExxonMobil, or BP whoever it might be, so maybe the people who don’t want to know have it right. Three, I am, therefore, trying not to be scared any more. Big ask, but I like a challenge and I only have so long left to live. MT: What are you writing next? Is there anything you’d want to share with our readers about a work in progress, or a book which isn’t published in the US, or is currently on the way to being published now? Can you give us any teasers, information that really will help keep us satisfied until the publication of your next work? MS: Ah, I was hoping you weren’t going to ask that, but I will answer as honestly as I can. I am not writing anything, and I am not sure why. It’s been three years now since I wrote anything that meant anything to me. I have had block in a serious way before, once for two years, and I came out of it, so I hope that will happen again. Since I always laugh at writers who have loudly and pompously declared that they will never write another book (who cares?!), only to promptly chug out a few more a year or two later, I would be a hypocrite if I did the same thing. (And anyway, who cares?!) And I understand the impulse when a writer makes this big declaration, to say this – because it really doesfeelright nowlike I will never write anything else. But this may of course quietly change one day, without fanfare or proclamation of any kind. I will be happy if it changes, but I will not die if it doesn’t. Since that isn’t going to please any readers of mine, the best thing I can suggest since you’re US based, is that I had a short book published in the UK a couple of years ago that for long and boring reasons didn’t get published in the States. So you could hunt that down. It’s called The Monsters We Deserve, and it’s to do with creativity, the lack of it, and who owns and owes what in the creation of a book. MT: Marcus, thank you so much for agreeing to be interviewed with Writers Tell All. We love your writing here, and I hope that our readers will go and pick up one or all of your books. They won’t regret a single read if it’s authored by you. Feel free to leave us with any comment or lingering thoughts or questions, or suggestions even. Thank you so much for stopping by, and we cannot wait for what you write next! MS: Thank you so much for having me. I saw that you ask great questions on your site and you certainly did, it’s a pleasure to be given the chance to get deep into question such as these. Thanks again, all the best, and I’m not sure I have anything else to add, apart from the fact that reading is even more important than ever right now, so please keep doing what you do.

0 Comments

Matthew Turbeville: We are so excited to talk to you about Harley in the Sky, an amazing book about a girl who may give up everything to pursue a dream. Can you tell us about how you came up with the idea for this novel and why you felt it is necessary to be told now? What do you feel when you know something—a book, a story—is necessary to be told?

Akemi Dawn Bowman: My first two novels revolved around abuse, trauma, and grief, so when it was time to draft my third book, I really just wanted to write something that would allow me to emotionally recharge. I wanted it to feel magical, while still being grounded in the real world. The circus felt like the perfect setting. And for me, I know a story needs to be told when it makes my heart light up. I’m someone who has a million ideas floating around, but for me to start working on one, I need to feel that spark. I like to think that if it feels important enough for me to want to write, then hopefully it will feel equally important to someone out there who eventually reads it. MT: The book is a mixture of genres, just like how Harley is a combination of so many races, backgrounds, cultures, and so on. What do you think this says about American youths today, and how does it reflect where our culture is or is headed? ADB: I can’t speak for anyone else, but for me this just felt normal. I’m multiracial, like Harley, and I’ve often struggled with feeling like I don’t “belong” to the cultures of my family. I’ve always felt like I wasn’t enough of any of the parts of my heritage, and that made it difficult to feel like I fit in anywhere. But I think maybe that’s the point—people similar to me don’t haveto fit in a box. We have a unique cultural experience, and we get to navigate that in new and personal ways. I think there are probably some interesting conversations to be had about what it means to have ownership over a culture, and how cultures grow and change over borders, generations, and time. MT: There are so many betrayals in the first part of the book. Some are heart wrenching, even when we dislike certain characters—perhaps every character—for deceit and a lack of loyalty on their part. Why do you think this is so important to a story about circuses, coming of age, and the other adventures associated with this? ADB: I like to think everyone has their own version of messy. It’s what makes us human. I write about characters making mistakes who are also trying their best because it feels real to me. Nobody in this world is perfect, and sometimes I think there’s too much of a spotlight on the mistakes people make rather than the journey that follows as a result of that mistake. People should be held accountable for the wrongs they do, but it’s also important to allow people to grow. Particularly when we’re talking about teenage characters, who are mostly still figuring things out as they transition into adulthood. I don’t expect my characters to be any more perfect than people in real life. And I think those coming of age themes will always feel timeless for that exact reason, regardless of whether they’re set in the circus or some other kind of adventure. MT: The beginning starts with family of many kinds—I believe Harley refers specifically to the biological family and the found family. Why is family so important in your novels, and is family important to you as a person? Do you think, in some ways, so many young adult novels are about family for a certain reason? ADB: Family is very important to me. The most important, really. But I also know that having a family is a privilege not everyone has. And I’m particularly aware of how that can feel for young people, who maybe don’t have parents who love them or a support system at home. It can be lonely, and extremely difficult to navigate, because there are so many emotions that come into play when you don’t have the kind of parental love that seems so normal to everyone else. Family is an important part of my novels because I want to give people hope, and let them know that even if they weren’t born with the family they needed, they can still find family through friendships. And I can’t speak for other authors, but it’s possible many of them write about family for similar reasons. Because whether someone has a family or feels the absence of a family, there’s a pretty good chance it plays a big role in that person’s life. MT: Harley’s parents come across as truly loving and caring for her and her future. Do you think there’s a right or wrong answer on either side, with Harley or her parents, and what do you think is so great about the way you write things and present all of these conflicting views? ADB: I think there are a lot of ways to be right and wrong. Sometimes what’s right for one person is completely wrong for another. And sometimes people can disagree, but both parties can still be right in how they feel. Not everything in life is black and white; maybe most things exist in a gray area. Hopefully this comes across through Harley and her parents, and the complicated relationships they have with one another (and Popo, too). MT: The ending also has a lot to deal with family, with dreams, and with both disappointment and success. Can you talk about the ending—perhaps without giving away too many spoilers—but essentially whether or not you think we find ourselves in a sort of reflection of the beginning of the novel, or what the ending means to young people pursuing their dreams? ADB: I’ll try to remain as spoiler-free as possible, but I like to think Harley fought hard to chase her dreams, and although the outcome wasn’t exactly what she’d planned in her head, she learned a lot about compromise and adjusting along the way. Even when we imagine our goals, it would be very hard to imagine the journey. Because the journey is often out of our control. Hopefully Harley’s story is a reminder for some people to be flexible, and to not be so hard on themselves and the people around them if things don’t go to plan. MT: My heart still breaks, even after finishing the novel, of a really horrible (in my opinion) betrayal Harley commits to get what she wants at the beginning of the novel. Do you think there are certain betrayals we cannot see past, and do you think it’s realistic for those affected by this portrayal to even want to have anything to do with Harley? While it makes sense in the book, obviously certain characters (and readers) my take issue with Harley’s actions, and I wonder what you think her actions say about Harley. ADB: Nobody gets through life without messing up. Sometimes it’s intentional, and maybe more often it’s by accident. But how we make amends, and how we turn the mistake into an opportunity to learn is so much more important, I think. Everyone gets to decide for themselves what they’re willing to forgive, and I could never make that decision for someone else. But Harley’s parents love her, and Harley knew she did something wrong. They worked through it in a way that felt right to them. I think perhaps any judgements towards Harley by the end of the book says more about a reader’s tolerance or limitations to forgiveness than they do about Harley. MT: What were the really formative books in your life, and what books and happenings in the real world and other media you’ve consumed that have helped informed Harley in the Sky? The book is brilliant, and I’m so interested into what books really affected this, even if they had nothing to do with circuses at all! ADB: I don’t know if this is just a “me” thing, but I’m not someone who can read other books when I’m drafting. I find it incredibly distracting, and I actively don’t want my writing to be influenced by anything else. I really lean into my own style of writing, because it feels natural to me. I have no idea if that’s a good or a bad thing, but it works for me. I will say though that there have been books over the years that have most definitely inspired me to want to be an author. Sometimes it’s the incredible worldbuilding, sometimes it’s the lyrical way someone can tell a story, but mostly it’s that magical feeling when a book comes to life, and characters feel real.That’s when I know a book is a gem. And it makes me want to write books that can be gems for other people. A recent favorite of mine that I will never stop talking about is THE PRIORY OF THE ORANGE TREE by Samantha Shannon. It’s truly a masterpiece. MT: What is editing like for you—well, really, the whole writing process? Do you write in a certain way, space, or place? Do you need to clear your mind or do you just write freely, not letting anything affect you? How is editing for you, and how many drafts do you go through before completing a novel? For books like Harley in the Sky where circuses are involved, how much research did you have to go into? ADB: I’m trying to be better at fast-drafting, mostly because I have multiple projects going on at once. My default style of drafting would slow everything down, as I’m someone who likes to edit as they write. In the past, I’d write a chapter, and then go back and edit line by line. But it isn’t necessarily the most time efficient work style, because I’m constantly making adjustments. Nowadays I try to just write as much as I can when I have the time available, because I know I can always go back and fix things. But I need to get the words down first. I tend to have a very skeletal outline, where I only really know the beginning, middle, and end. And HARLEY IN THE SKY went through many rounds of revisions—several on my own, and then several more with my editor. I also did alot of research when it came to the circus life aspect in Harley’s story. Originally, the circus was meant to travel by train, and I watched an entire documentary on what that looked like. But ultimately it didn’t feel right for the story, as I wanted the characters to explore the world a bit more. I also watched more trapeze clips on YouTube than I can even count, and read many, many articles on circus life. It was a lot of fun to research! MT: What other young adult, and perhaps adult or middle grade books and authors would you suggest to readers of Harley in the Sky? I’m sure this book is developing quite the fanbase, especially with such high praise from critics including myself, and I wonder if there are any other authors you might recommend while we wait on the next great novel from you! ADB: DON’T READ THE COMMENTS by Eric Smith, I’LL BE THE ONE by Lyla Lee (which comes out later this year!), THE ASTONISHING COLOR OF AFTER by Emily X.R. Pan, and anything by Ashley Herring Blake, Sara Barnard, and Brandy Colbert. MT: What do you think this says about young women too, throughout the book, and in the many compromising positions Harley is forced to deal with as she navigates her way through this part in her life? What about seeing the world and really trying to commit to something affects Harley as a young woman? ADB: I think there are a lot of important discussions about how we view women when it comes to having aspirations or goals that are long overdue. It’s also why I find it interesting that people would feel so unforgiving towards Harley. Because I’m not sure male characters are held to the same standards of morality and perfection. There are countless novels that exist where male characters make mistakes, are morally gray, or are even unapologetically the villain, and yet there are people who love them despite their flaws. And then there’s someone like Harley, who makes a mistake, acknowledges it, and tries to make amends in ways that feel right to her, but is put into a category of unforgiveable behavior. I think that speaks to real-life, and the double standards that exist when it comes to gender. MT: Do you have another work in progress? Can you tell us anything about it, and what we can expect in your next work, and when to expect it? ADB: I do! I’m actually working on two projects at the minute. The next book that’s set to publish is my sci-fi debut called THE INFINITY COURTS. It’s about a girl who dies and wakes up in the afterlife, only to discover it’s been taken over by an artificial intelligence posing as a queen. It combines my love of robots and superpowers with Jane Austen and period dramas, and I’m seriously so, so excited to share more soon. I also just turned in edits on my middle-grade debut called GENERATION MISFITS, which is about a group of sixth graders who meet through a shared love of J-Pop. It has Breakfast Club vibes, but with all the heart and worries of being eleven years old at a new school where all you want is to make friends. It’s very close to my heart! Both are set to publish in 2021. MT: Thank you so much for joining us and talking to us about Harley in the Sky. We at Writers Tell All truly loved the book and cannot wait to read more from you. Please feel free to comment on anything you feel we didn’t touch on, or you want to elaborate on below. Thank you so much for agreeing to talk to us, and thank you for this book. It is phenomenal and we hope all of our readers will pick up a copy and dig in to Harley’s story! ADB: Thank you so much for chatting with me, and for all your thoughtful questions! Matthew Turbeville: I am so excited to get to talk to you about these genre crossing, nail-biting, beautiful and unforgettable novels with you. My first question regards your actual writing style though: when do you decide an idea is right, how do you decide it’s something you want to pursue longform and long-term and what is your writing process like? (Morning/night writer, how your revisions go, where you like to write, by hand or computer or otherwise?)

Yangsze Choo: Thank you so much for having me! I wish I could tell you that I get up every morning at five, exercise enthusiastically, and then sit down to write, but the truth is far more mundane and disorganized. Mostly, I feel that I’m bumbling around, doing housework and making repeated visits to the refrigerator for “inspiration”, all while yelling at my kids to pick up their clothes… In order to write, or perhaps be any kind of creative (which includes drawing/painting/building bicycles etc.) I think one needs a lot of blank, empty space. For me, that translates to silence, so unfortunately I have been relegated to writing late at night after the house is quiet and my kids have gone to bed. This is terrible because I’m actually a morning person and don’t like being up late at night. There have been times when I was writing certain ghostly passages in The Night Tiger when I frightened myself and had to eat large quantities of chocolate in order to recover. I write organically (that is to say by the seat of my pants) and often discover the story as I write it. This is why it takes so long for me to write books. The Ghost Bride took about five years, and The Night Tiger four years. MT: What authors inspired The Night Tiger and The Ghost Bride? What authors today helped you develop your own voice as a writer and author these great, now well-known novels? What book or author do you feel helped you grow most as a creator? YC: There are so many writers that I adore—Haruki Murakami, Isak Dinesen, Susanna Clarke, Yoko Ogawa, Tana French—to name just a few. I think what they all have in common is the ability to transport the reader to a completely different world, where snow is falling outside a grand house in Copenhagen, or a professor who has lost his memory and experiences each day anew. When you read a really good book, there’s this frisson of excitement when you snuggle in deeper into the story and fall into another world, forgetting all that is before you and becoming someone else for a little time. That’s the magic of reading. I hope we never lose it. MT: You have a lot of the mystical and magic in your writing—there’s horror, there is this place between magical realism and fantasy, and you balance everything so well. How do you feel this differs from other writers, and how do you manage to balance so many elements so well? You can easily move from one genre to another, combining all into one supergenre, the great Yangsze Choo novel. How did your own type of novel come about? YC: Thank you for your kind words—I’m so delighted and honoured that you enjoyed my books! Actually when I started writing, I just wanted to write a story that seemed interesting to me. So I put in all these elements, including dreams, ghosts, and promises. Also, murder mysteries! I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of parallel or mirror worlds—places where things are not what they seem, whether that’s the Chinese world of the dead, or a dream world where people talk to you in deserted railway stations. Speaking of railway stations, I remember very clearly traveling by train from Kuala Lumpur to Singapore, in those days when we still had the old trains and it took about eight or nine hours, rattling along very slowly and stopping at all these small towns. There was something both magical and tedious about such a journey, watching the towns appear and disappear, and long stretches of the track winding through green jungle, all while looking out for interesting landmarks. That, and my own nostalgia for a historic Malaya long gone, led to many of the elements in The Night Tiger. In some ways, you could say that all novels are a journey of some sort, and The Night Tiger in particular does remind me of one. The strange occurrences in the book are like landmarks or signals that you watch out for from a train window. And from time to time, a door opens or closes to somewhere new. MT: Speaking of your own type of novel, how hard is it for someone—an author, any author—to invent a way of writing all their own, and outside of yourself, who do you think is the most creative and unique in telling stories today? YC: I am a huge, huge fan of Susanna Clarke (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell). The first time I saw that book, it was in huge pile stacked in the front of a bookstore. I didn’t know anything about her or the book, which had just been published. They had two colours of the hardcover, so I seized one, flipped through the first page, then bought it to take home, where I spent the next two days devouring it. That is a very happy memory and one that I’m sure fellow book lovers have also experienced with different novels—that sensation of discovering something new and wondrous, a world that you had no idea existed. That’s the kind of feeling that I would love to give readers in turn. MT: You talk a lot about curses, ghosts, magic, fate—what draws you to these ideas, and why do you think they’re important today? When looking at these recurring ideas and themes in your novels, what do you feel you want the reader to take away from the novel upon finishing the book? YC: Sometimes I wonder whether we are continuously writing the same book, or the same story: exploring, turning, and examining it anew. I’m a huge fan of Haruki Murakami’s, and I get that feeling from his novels. Yet I really enjoy them and love being immersed in his world and prose. Mirror or parallel worlds has been a theme for my own writing, and how we as humans can accept the existence of completely contradictory ideas (ghosts and dream messages, interspersed with scientific data!) and be emotionally ok with all of them. Part of this is the world that exists in your own head; one where events move towards a purpose that may exist or not—who is to say which one feels more real to you? That is the dream-like feeling that I think we all occasionally get and that I’ve tried to capture in my books. It is an escape and also a terror and delight. MT: Which book was the hardest to write? What do you find makes things hardest to write for you, and how do you get over these hurdles and to the finish line—and so well! YC: I’ve only written two books so far (though I’m working on a third right now), but I’d say that The Night Tiger was harder to write than The Ghost Bride, partly because it was such a complicated and ambitious narrative, weaving two storylines together at once. It also covered a number of subjects—colonialism, men and women, foreigners and locals, dreams and reality—that I’m still vaguely shocked that I managed to squeeze them in! People have asked me whether I wrote each story out separately, and then put them together. The sad reality is that I’m not organized enough to do something like that. I wrote the whole book pretty much as the reader experiences it—one chapter at a time, swapping out the narratives. Part of it is that I didn’t know what was going to happen next, so I really couldn’t plan. This absence of outlining has been both my bane and a source of unexpected joy. MT: There are also elements of lots of crime, intrigue, and mystery in your novels. What do you think is so important about writing of crime in today’s world? What are your favorite crime novels, and do you believe every novel is, essentially, a mystery? YC: My youth was spent reading pretty much every Agatha Christie novel I could get hold of, and later on, other favourites include PD James, Ian Rankin, and Tana French among others. I do think that all good books contain some sort of mystery, though it appears in different guises. Whether it is the unraveling of a relationship, the demise of a dream, or the discovery of a dead body… the mystery is what calls out to us as readers to examine and explore, not just the world of the novel, but our own hearts as well. MT: What are the connections between your novels? How do you feel they play together versus separately? Do you feel like you made a natural transition from one book to another easily? Which book is your favorite, and which was hardest to accomplish? YC: I once heard a great quote from Elmore Leonard when he was interviewed on NPR. When asked which was his favourite book, he replied “the one I’m working on”. I thought that’s so helpful—you have to love the book that you’re currently working on, otherwise you’ll be tempted to give up (I know I often am!). In terms of the two books I’ve completed so far, I’d have to say The Night Tiger is my favourite, and was also the harder one to write. As I mentioned earlier, that’s partly because it was much more ambitious than The Ghost Bride. Also, I noticed later that I tried to write each novel in very much the historic vein appropriate to its time period, so The Ghost Bride is written as a Victorian Gothic novel, with vocabulary and imagery. One thing that I enjoyed about writing The Ghost Bride was being immersed in the Chinese world of the dead, with its antiquated imagery (even for that time), and burned paper offerings. It’s a world rich with superstition and ritual, where cultural expectations constrain behaviour. Yet that was also a little difficult to deal with in terms of plot, as I tried to keep my protagonist, Li Lan, historically accurate to a sheltered girl from a once-wealthy family. I was also learning about pacing and plot as I wrote that book, and there are definitely things I would have done differently if I had to rewrite it today! But I suppose all writers feel like that to some extent—a novel is never quite “done” or good enough. The Night Tiger is set in 1931, when they had electricity and trains, so that was a lot more entertaining to write about! I’d read Somerset Maugham growing up, which helped with the background of colonial Malaya, and I have also always loved the crumbling, gracious colonial bungalows left over from that era in Malaysia. One thing I noted was that 1931 was closer to the 1920s in terms of fashion and popular culture. Beyond that, the fact that The Night Tiger is a dual narrative allowed me to play around with characters and setting in a faster and more complicated way. I really enjoyed that, though it was also rather challenging. MT: Some authors are outspoken about the number of books a writer should author in a certain period of time. Do you ever say, “Hey, I’m moving too fast” or have any beliefs of your own? How long does each book take you, and how many more books do you have in you currently? I know I have a thousand books fighting in my own head, waiting to be written. YC: Oh dear, I’m afraid I’m a very slow writer. I often feel terribly guilty about that. It took me about five years to write The Ghost Bride, and four for The Night Tiger. In between, I got stuck and had to put each novel aside for a while when I ran out of ideas. A great deal of fiction writing for me occurs off the page, when I’m walking around or doing something mindless, and an idea will pop up. That’s the best feeling, though it doesn’t always happen and sometimes I go for long periods of drought. It’s very hard to sit down and write. I know other people who are much more disciplined and can do this, but for me, the creative process requires a lot of empty space, including silence. That’s very hard when you have kids barreling around the house and shouting! MT: With violence, with crime, we also see magic related between the two, and controlling the two, in your novels. What do you feel is the connection between these elements, specifically magic and mysticism and crime? YC: I’ve always thought that detective stories and ghost stories are basically the same, except that they start at different ends of the tale. Both address the mystery of a crime or someone’s passage into death, and both require an audience or a detective to unravel what happened. And in the end, there is some sort of resolution or reason. The magical part, I suppose, comes from our wishful desire to know exactly what happened, and that can manifest in many ways, from a talking crow to a message from the dead. Or perhaps, it is simply the possibility of a neatly wrapped answer. MT: What do you have planned next? Is there a book being published, a work in progress, or some other book we should be looking forward to which is only in your head for now? YC: I’m currently working on a third novel, which I’m excited, hopeful, and despairing of, depending on which day (or time of day!) you talk to me. The story itself is still being formed, but I wanted to write about snow and a cold climate. I spent part of my childhood in both Germany and Japan, and some of the most vivid and poignant memories I have are of snow falling. The silence, the soft cold, and the feeling that the whole world was being made anew when you woke up to a thick blanket of snow. So I started off by setting my new book in Manchuria (northern China) in 1908, but we’ll see where it goes. I’m still trying to figure that out! MT: Thank you so much for being interviewed by us at Writers Tell All! We are so happy to have read your books and look forward to reading much more from you in years to come. Please feel free to stop by any time, as we will always be fans, and please let me know below if you have any thoughts, questions, concerns, or comments you want to share with our reader. Thank you so much! YC: It’s been my pleasure and honour. These were such fun and wonderful questions. Thank you very much for having me! Matthew Turbeville: Hi Sheena! Before I get started on the novel, I wanted to hear about your background with writing—how did you start writing fiction, and how many novels did you author (or revisions gone through) before you published your first novel?

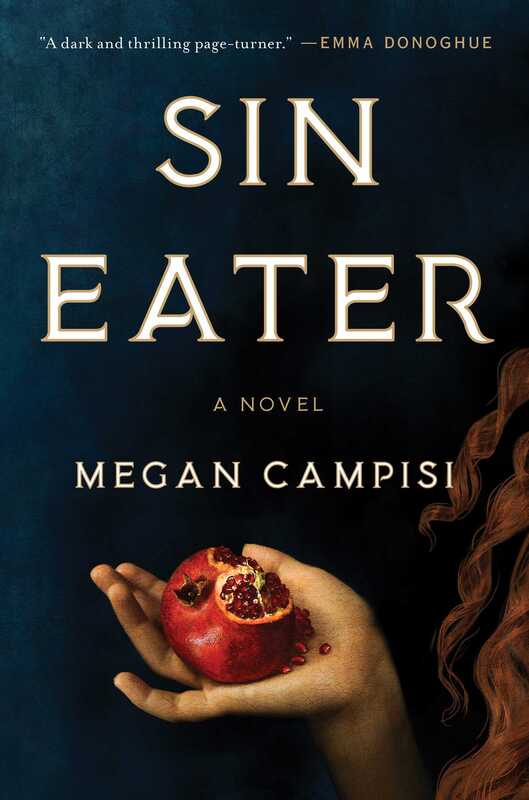

Sheena Kamal: Hi Matthew! My background is all over the place, but right before I wrote my first novel, The Lost Ones, I was working in film and television. Sometimes as an actor, and then sometimes on the production side of things. The aim was screenwriting, but it never worked out. The Lost Oneswas the first novel I attempted, and I wrote it in about eight months. I didn’t do much revising before pitching to agents. Once I had one, I revised it once and it sold. Then I did another revision for my publishers. MT: Who are your favorite crime writers? What about your favorite writers in general? What authors shaped you during your formative years, and what book or books do you turn to if you ever get stuck in a novel, need a fresh way of viewing something, or just want to reread a book in general? SK: I love Attica Locke, Liz Nugent, and Alison Gaylin. Writers in general… there are so many. My new favorites are Sally Rooney and Oyinkan Braithwaite. The book I turn to most often is The English Patient, by Michael Ondaatje. There’s something about the language in it that I find incredibly beautiful. It always unlocks something inside me, just by immersing myself in his prose. MT: What is your writing process like in general? Do you write by hand or do you write on a computer, or some other way? Do you tend to write everything out at once or edit as you go? What are your writing habits like? SK: I write daily, on my laptop. When I’m on the go, I usually have a notebook to jot ideas down in, but my handwriting is almost illegible, so not much is accomplished there, I’m afraid. I edit as I go, usually. MT: I don’t want to give away too many spoilers, but will you tell our readers a bit about what your new novel concerns, where we find Nora (if you think that should be given away), and for fun, how it ranks for you out of the novels you have published so far? SK: Ha! It’s impossible to rank your babies. I think the ending of my latest Nora Watts novel is the best ending I’ve ever written, though, and for me there’s definitely something special about that. In No Going Back,Nora realizes a shadowy figure from her past is hunting her, and this threatens the life of Nora’s daughter Bonnie. Nora has to find him first, to protect both her and her daughter’s life. MT: How did you come up with Nora Watts, and how far did you see her story going from the first book? Was there ever initially meant to be more than just a “book one”? SK: Nora came to me one day as I was sitting in a television production office in Toronto. I didn’t set out to write more than one book at that time. I just wanted to see this idea to fruition. It was my first novel, and I wasn’t thinking beyond the task of getting it done. Once it was on submission with publishers, however, I realized it could have more life to it and I started to think beyond the first book. MT: What do you think draws you back to Nora again and again? How did you develop her voice and learn who she was through your writing? How hard is it to catch a voice for a character, to grow a unique personality, and how does one character shape or mold to fit a story or character they might be attracted to or opposed to? SK: I didn’t develop Nora’s voice so much as I followed it by instinct. That’s what draws me to her, really. I can always pick up her voice, so it’s very natural to me. MT: What’s the hardest part about writing in general, and what’s the hardest part about writing Nora? Do you ever feel she takes the story in places you don’t want the novel to go? What are your favorite parts about writing Nora? SK: Writing is a daily slog, isn’t it? But I love it and wouldn’t see my life any other way. Nora constantly surprises me, so writing her always feels like she’s taking the novel far away from the outline I’ve submitted to my publishers. MT: What’s one thing you want readers to take away from your novels, especially No Going Back, other than a fun reading experience? SK: Ultimately, I want them to be entertained, and love Nora as much as I do. MT: What do you hope Noratakes away from the book? SK: Oh, man. I want her to have some peace. I want her to be happy and start eating healthier. I want her to trust people more and do things that bring her joy. Obviously, these things aren’t going to happen, but I can only hope. MT: Have you ever written something that’s shocked you, either about a character or even yourself? What is writing like for you as a personal journey? SK: I mentioned this briefly earlier, but the end of No Going Backshocked me. I can’t really talk about it without giving it away, though. As for writing, it’s the tool I use to understand the world, and a huge part of my personal journey. MT: Have you ever been emotionally struck or stuck during the writing process, and has there ever been a part of writing—a scene, a character, an event in a book—which has proven particularly difficult for you emotionally speaking? SK: Yes, it’s all difficult emotionally speaking, because I write first person, present tense. At times it feels like things in the novel are happening to me. It’s just the way my imagination works. MT: Say you had a super team of private investigators and ongoing series characters, recent or not. The Avengers of the crime world, say. Who would you put together and why and how would they fit together? SK: I would have a crime fighting duo. Sara Gran’s Claire DeWitt and Lisbeth Salandar. I think those two would have the most deliciously antagonistic chemistry, and I would love to see a mystery unfold with those two at the helm. MT: A lot of people attribute the quote about writing the book you’ve never found but always wanted to read to Toni Morrison. Do you feel you’ve written or read that book yet, and if you haven’t, what might that book be like? SK: I think that about all my books, because they are so unique to me, my experiences and my worldview. And what I want to write about changes as I change. MT: What are you writing currently? Do you have another work-in-progress ready, and how is your work responding to what’s going on around the world currently? SK: I am polishing a draft of a novel to send to my agents. It should be ready soon. I think the landscape is going to change, absolutely, but since this book isn’t political—the crime it deals with is very personal—I think it will be fine. How my work responds to the current situation in the world will adapt as I understand the fallout of what we’re going through. But I’m not there yet. MT: Thank you so much for speaking with us, Sheena. I can’t wait to see what comes out of the rest of your career, which I know will be explosive and packed full of tons of great books. I’m so thankful you’ve talked with us, and feel free to leave any lingering thoughts, ideas, or messages with readers and fans! Thank you again, Sheena. SK: Thank you for having me! I wish you all the very best, and hope you stay safe and healthy.  Matthew Turbeville: Hi Megan! I’m so glad I got to reach out to you about your marvelous new novel Sin Eater. Before I begin with the questions, can you tell us a little about the novel and why you felt it was so important to write this novel now? Megan Campisi: Sin Eateris a historical fiction mystery set in a reimagined Elizabethan England. It follows 14-year-old May Owens who is condemned to be a sin eater. In this role, she hears deathbed confessions and, at the funeral, eats ritual foods representing the confessed sins on the dead’s coffin, thereby taking the sins onto her own soul. As a sin eater, she becomes a pariah in her own community. But as the novel progresses, she turns this curse into an unexpected source of power. She uncovers a series of murders that reach all the way to the queen and sets out to solve them using her untouchable status. It’s a story about an isolated young woman finding her strength and also finding her people. While Sin Eater’s story is proving very timely (a young woman persevering through intense isolation), the reason I wrote the book when I did was very practical. My background is in theater, and I am mostly a playwright. When my first child was born, getting to rehearsals in addition to my day job (teaching at a theater conservatory) became so challenging, I decided to give long-form prose a try. I had been mulling over writing a coming-of-age historical mystery with a sin eater protagonist, and it seemed like the perfect project for the moment. MT: I was pulled into this book, in a way I was pulled into some books by Avi when I was younger, and some other books with historical settings by adult authors like Lyndsay Faye. One really captivating way was how you were able to use different forms of language but still captivate the reader—how do you feel you did this effectively, what was your greatest struggle with establishing this strong sense of language? MC: In creating the language of Sin Eater, I was inspired by nursery rhymes and fairy tales. For me, nursery rhymes are magical snippets of cultural history that get passed down from generation to generation like a game of telephone. And like telephone, the story becomes distorted as one generation shares it with the next. Some words remain the same, but others lose their meaning or take on new meanings. I’ve always loved this mix of mystery, invention, and history. I’ve tried to bring those qualities to Sin Eater. MT: Similarly, you also had a strong sense of character for the protagonist, May, and who she was from the very beginning. Can you describe you develop character, and how long it took to find a voice and character for Meg? Did you develop the book from character, or develop the character from the book? MC:The story and main character evolved in relation to one another. I knew I wanted May to be a “late bloomer” and possess a vulnerability that made me protective of her. At the same time, I wanted her to be resourceful and resilient. It took time to find that balance. Similarly, her journey follows the transformation in how she sees herself, the world, and her place in it. I tinkered with that journey throughout the writing and editing processes. MT: Where did the idea of a “sin eater” come from? How did the idea evolve—from sins translating to food, and women responsible for eating these sins? How did you relate all of this back to Eve? MC: I’m a history nerd, so when I encountered sin eaters, I was hooked. But for my story to work, it couldn’t remain a post-mortem ritual, as it was historically. Sin eating needed to be a deep communion between two people that was woven into the fabric of society. The ideas evolved from there. Eve seemed like the perfect representation of Lucifer in this “alt history” because she embodies the Christian concept of original sin. MT: What books and authors influenced Sin Eater most? What books, authors, and genres influenced you most during your formative years, and what book or author influenced you most in general, and is your favorite? MC: For Sin Eater, I was influenced by historical fiction writers like Peter Carey and mystery writers like C.J. Sansom. As a child, I loved Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicornand M.M. Kaye’s The Ordinary Princess. As for a favorite author, it’s so hard to choose. I am a huge fan of David Mitchell and George Orwell. But if I have to choose just one author, it’s Toni Morrison. MT: May has a clear understanding at one point of the book that there is a concept of light and darkness within every person. What do you think is important about this concept and why is it so important to who May is? MC: Good and evil were concepts that occupied a lot of my thoughts as a child (I was raised Catholic). It took me many years to understand how subjective these qualities are, and that my own view mattered. That, to me, is the heart of May’s journey. MT: What do you want readers to ultimately take away from Sin Eater, and why do you feel this is important in today’s world? What do you think is the most important part of Sin Eaterand how did you come across this idea, theme, or subject in your writing of the book? MC: May’s story is about deciding who you are for yourself and about finding your people. These themes are deeply rooted in my own experience growing up and choosing to lapse as a Catholic. MT: What is your writing process like? Are you a big planner? Do you outline or write as you go? How many rewrites and revisions do you go through in your rewriting process? How long did it take to make Sin Eaterthe amazing book it is today? MC: I’m a visual, physical person. When I outline, I paste sticky notes all over a large board. Then I can “see” the plot and move it around as I like. As for my process, I write whenever I can, as much as I can. When I began Sin Eater, my first child was nine months old, I was pregnant with my second child, and I had a full-time job teaching at a theater conservatory. I couldn’t be precious about when, where, and how I wrote. It took two and half years to write the book. The last six months was just editing. MT: There are strong connections to Christianity and Christians both then (the historical period when Sin Eatermight be set) and now, and there are strong connections to cult thinking, and the way we are affected by cult mentality. What’s so important about the reason young and older people need to think for themselves and not fall into a cult way of thinking, and what do you think May is in this type of thinking, and does she defy cult thinking or does she play into it over the course of the book? MC: This gets back to what I want people to take away from the story:May learns to decide who she is for herself. She also finds a community that accepts her for who she is. MT: What was your favorite part about writing this book, and what was the hardest part about writing Sin Eater? Were they the same thing? What did you learn from writing Sin Eaterand are there any parts of the writing process you’d never want to go through again? MC: I love world-building. Creating the “alt history” was a pleasure. The hardest part was the mystery: it took time to figure out how much to reveal when. I learned so much from the process, but would gladly do it all again. I truly loved writing the book. MT: Were there any parts of the book you felt you had to fight to keep in place when writing the novel? Were there any parts of the book you didn’t want to keep in the book that are now a part of the final product? MC: The editing process was remarkably smooth (in large part thanks to my fabulous editor, Trish Todd,at Atria Books.) The published book completely reflects my choices. MT: Would you ever return to the world of Sin Eater in your future books? MC: I don’t have any plans to right now. MT: Do you have a new work in progress or a book on the way to being published? I know I for one cannot wait to read whatever you publish next. Will you give us any hint to what this next book or work in general may be about? MC: I work on multiple things at once. One is another historical fiction novel about women spies in the American Civil War. It centers on women’s relationships with each other across a deep political divide and whether that divide can be bridged—something that’s been on my mind a lot lately. MT: In May’s world, and in Sin Eater, whether resulting in death or just the testing of morals and ethics, what do you feel is the greatest crime in the book, and why do you feel it’s so important to readers? MC: The greatest crime is a society taking away a person’s voice and personhood. In Sin Eater, I’ve tried to chart an individual revolution in the way one woman sees herself to remind people that change can start at home and grow from there. MT: I loved your book so much, Megan, and I’m so glad you agreed to talk about the book with us. We are so thrilled to have you talk to Writers Tell All. We wish you the most success with this book. Feel free to leave us with any lingering thoughts or ideas you feel weren’t discussed or talked about in depth, and thank you again for working with us and being involved in an interview for this website. We loved your book and encourage all of our readers to buy or preorder and read this book! MC: Thanks so much for reading and for your great questions!! Stay safe and well! Megan Campisi is a playwright, novelist, and teacher. Her plays have been performed in China, France, and the United States. She attended Yale University and the L’École International de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq. The author of Sin Eater, she lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her family. I had the amazing opportunity to sit and talk with Robert Doyle about his new novel, Threshold, which I'd describe as a nice collision (it's intense at times, which is great) between the odd and vivid writings of Marilynne Robinson, the more autobiographical novels of Mario Vargas Llosa (more Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter), and some of the philosophical nature of writers like Iris Murdoch (only sadly without the murders and suicides and dramatic plot twists!). A brilliant book, something to consume slowly and all at once, Threshold is yet another reason to contact your local indie bookstore and purchase something by a great writer.