WRITERS TELL ALL

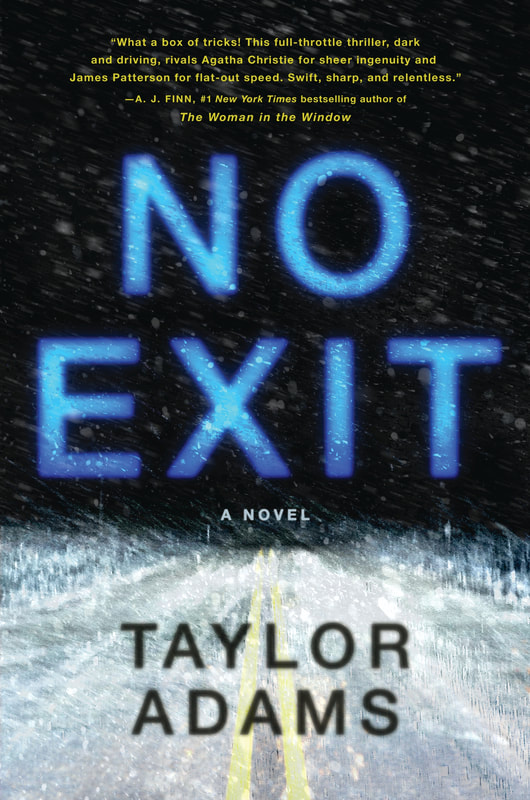

Followers of the site and my other writings elsewhere will note that I rarely endorse a novel so wholly, and yet NO EXIT is the novel to beat this year, and perhaps this decade. An astonishing novel of a young woman's desire to survive, and will to save another life, is so astonishing, nail-biting, edge-of-your-seat (and all other cliches), it is irresistible. But rest assured that NO EXIT is no cliche. It is phenomenal. Below is my interview with author Taylor Adams. Matthew Turbeville: Wow, Taylor, this is a remarkable novel. I very rarely read books that completely overwhelm me with the story and characters. The book feels like a non-stop action ride peppered with some really great characters and a lot of other interesting things as well. What did you have planned when you first came up with No Exitand decided to write the book? Taylor Adams: Thank you! I love contained thrillers, and I’d really wanted to try my hand at writing a story that took place in a “locked room” with very little outside interference. I think the pressure of isolation can do wonders for a story’s tension, and rest stops had always struck me as naturally eerie places. The idea of witnessing a horrible crime at a rest stop – and being trapped with the evildoer due to outside forces – was just too exciting a premise for me to ignore! MT: Darby is such a wonderful character. I don’t know how to describe her—and given the obstacles in her way, her will to survive—I have to ask what went into making Darby as a character, and how did you decide this was the challenge she would face, and that this would be the perfect fight for her to take on? TA: Darby was a fun character to write. I knew from the premise that the story needed a heroine who appears ordinary at first glance – but as she’s put to the test, she surprises herself, and the villain, with shocking tenacity and courage. That kind of heroism is genuinely inspiring to me. And I also tend to empathize with characters who are in a situation hopelessly over their heads (not sure what that says about me!). Throughout the rewriting process of No Exit, I frequently reminded myself: Darby isn’t a cop, she doesn’t know any martial arts, she’s not even particularly strong – but to save a little girl’s life tonight, she will literally cut throats. I love that in a protagonist. MT: There are so many twists, some fairly early on. I know reading this book I felt settled in and cozy, not because the book was happy or I thought it would happily, but because I really believed I was reading a story being handled by a master of the form. How did you introduce these twists, and during revision and rewriting were there ever times you really felt that you needed to add or remove something significant? TA: The story was more straightforward in its earlier drafts and became “twistier” as I rewrote it and found new opportunities for misdirection and surprise. Particularly in the final third, I really felt the need to layer in the upsets, as I feared the ending wasn’t packing the punch it needed to. One particular late-game twist – involving the outside world’s response to the climactic bloodbath – is one that I’ve been wanting to use in a story for years, and finally had the chance to! But on the other hand, overdoing it can feel like narrative whiplash. There was a final planned twist to the story’s epilogue which I’d struggled valiantly to write for several months before realizing it was simply too much. It would have been a major misstep. MT: This novel reminds me so much of Joe Hill’s NOS4A2, in so many ways, although it is a book all its own. What are the books and authors who really influenced you and your writing throughout the creation of this book? Were there any books you particularly turned to when you were having an especially hard time writing the novel? TA: I’m so happy to hear that! Joe Hill was absolutely an influence, as was much of Stephen King’s work. They both have an effortless way with the poetry of terror. I’m also a big fan of Scott Smith, whose amazing novels The Ruins and A Simple Plan similarly involve small groups of people under extreme pressure. And I’d be remiss not to cite the classic Christmas story Die Hard as a major influence – I wouldn’t quite call Darby a female version of John McClane, but I like to think they’d get along. MT: What are your writing habits actually like? Do you write in the morning, evening, night, or are you the type of writer who fits writing in whenever you can? What was your path in becoming a writer, or did you feel this was always your “calling”? TA: I like to write in the mornings (preferably with about a gallon of black coffee). I find I’m much sharper and more focused in the early parts of the day, so getting my obligatory thousand words in right at the crack of dawn is best. From an early age I knew I wanted to be a writer – when I was five years old, my parents bought me this publishing service for kids where you write/draw the pages and publisher binds it together as a book. Five-year-old me wrote “The Train’s Worst Day,” a harrowing and surprisingly bleak story about a train struggling to get home amid an onslaught of natural disasters. I guess I’ve always had a thing for tormenting my protagonists. MT: This novel feels like it is about some really strong women—Darby in particular—and the determined need to survive and see things through to the end. The ending is something that I’m still trying to wrap my head around, and also something I loved and admire you for so immensely. If you wouldn’t mind sharing, who are the women who have affected your life deeply and influenced Darby—personal, literary, famous, activists, so on? TA: My wonderful girlfriend Jaclyn was a tremendous influence. She’s an extremely smart and tenacious attorney, and she takes no crap in a legal field that’s still heavily male-dominated. Likewise, in No Exit, Darby assumes an action-hero role, which is perhaps an equally male-dominated space. Her enemy underestimates her at first. But she digs in, duct-tapes her wounds, plans her attack, and does not quit. That’s Jaclyn, winning a case. MT: This book is much more a thriller than a mystery (although there are some really great elements involving mysteries as well in the book). What’s so amazing is how you kept me glued to the page, unable to stop reading until the very last sentence, and even then wanting more. My heart was pounding, my fingers curved in and digging into the page, and I knew this would be a book I would think about for days. What are a few of your secrets to maintaining such incredible suspense throughout the entire novel? It’s astounding how you were able to make use of every single word in the book—something most writers don’t have the ability to do—and even from the first page. Can you explain how some of this works? TA: Momentum is extremely important to me. Whether it’s a gentle pull or a sharp tug, I truly delight in the sensation of a story relentlessly pulling me to the next page. I worked hard to keep that momentum unbroken throughout No Exitby keeping the tempo varied and making sure Darby never has a chance to rest (in fact, an early title was No Rest). When writing the action scenes, I tried to visualize the events like a continuous camera-take in a film, following clear lines of cause and effect for clarity and urgency. Even the simpler things like chapter transitions – for example, making one scene’s ending “rhyme” with the next scene’s beginning – can be a powerful tool for keeping that all-important momentum unbroken. MT: At times, I suppose it seems like Darby is fighting for her own survival, but in others ways we see Darby fighting to survive and “win” (that’s the term I’ll use for now so I don’t spoil the book) and I wonder what “ghosts” you give your protagonists, what things haunt them and drive them, and what are the aspects you add into the novel in the current situation that drive the protagonist even harder? There is a person Darby is trying to protect, and I wonder what this person represents to Darby? TA: As exciting as fighting for survival can be, it will quickly become boring if spread uninterrupted over 300+ pages with no other character motivations (believe me, I’ve tried!). It’s important that the hero have other emotional needs that can serve to both mix up the stakes and deepen the story’s primary conflict. In this case, Darby’s guilt over her troubled relationship with her mother, and her limited time to make amends, provides a brutal added stress – and ultimately, a very positive route toward redemption. MT: If you do outline your novels, how do you do it? If you don’t outline your novels, what is the process like? What do you focus on first, character or plot? What helps to pull you in to a story you’re creating to make a truly great novel? TA: Oh man, do I love outlines. I’ll often outline many times before writing a first draft, and even between drafts. They’re a great way for me to get my head around a story’s shape and structure. I would say I focus on the plot first – in a novel like No Exit, the plot is basically the situation, and the changing situation is what informs the characters’ goals (good and evil alike). As the story takes shape, there needs to be an emotional core to hero that I can connect with – in the case of No Exit, it’s Darby’s determination to make a difference and defy her own selfish past, even if it’s literally the last thing she does. That’s the “fuel” for me. MT: Your novel does not stop from its very beginning until its very end. As I mentioned before, you make use of every word in the novel. I have to wonder how long it took you to write this novel. What was plotting every twist and turn like when there were so many and you made every sentence and word count? TA: It took me a good eighteen months to write No Exit, across numerous rewrites, overhauls, and general fretting. I started every draft as a new Word document, refocusing and distilling the story each time, to find the most efficient ways forward without breaking that all-important momentum. In many ways, that rapid pace came at the cost of character development – I had scarce time to delve into anyone’s backstories – so I worked hard to show their traits in action instead. MT: I have to ask, do you have any other books coming up soon? A work in progress or a book that is ready for publication soon? I’m sure our readers will be dying to know. TA: I do! I’m hard at work writing another twisty thriller with the working title of Hairpin Bridge. It follows a young woman hellbent on proving that her twin sister’s shocking suicide, atop a remote bridge in Montana, was really a murder. To prove this, she drives out to that very same bridge and interviews the local cop who claims to have discovered her sister’s body, and tries to catch him in a lie… MT: Taylor, thank you so much for letting us pick your brain about your book. It was an endlessly entertaining, beautiful, brutal, visceral, and frighteningly good novel to dive into and I’m so glad I got the chance to read it—and let us know if you have any thoughts, comments, etc below. Thank you again! TA; Thank you so much for having me here! I really appreciate the kind words!

0 Comments

Barry Eisler on THE KILLER COLLECTIVE and Writing Amazing Characters and Being Incredibly Prolific1/22/2019 Matthew Turbeville: Hi Barry! Before I begin talking about Livia Lone and maybe a bit about John Rain, I wanted to know about your history in work and life before you became an amazing publishedauthor. Can you tell us a little bit about what your life was like before writing?

Barry Eisler: Mostly I was a writer/philosopher/adventurer trapped in a lawyer’s body…J Joking aside, in retrospect it can all look planned because my previous experiences tend to manifest themselves in the stories I write, but I was really just bouncing around, not sure of what I wanted to be, what was best in me, where I could make the most meaningful contribution. I spent three years in a covert position in the CIA; then I was a technology lawyer in Silicon Valley and Japan; then I was an executive in a Silicon Valley startup. Some of it was interesting, some less so, but I guess all of it was redeemed to at least some extent by being transformed into fuel for my stories. But the truth is, I’m still not satisfied I’m really doing what I’m best at and what could make the biggest impact. Before being hounded to death by the U.S. government, Aaron Swartzsaid, “What is the most important thing you could be working on in the world right now? And if you’re not working on that, why aren’t you?” I think about that a lot, and I’m not sure whether for me writing novels is the answer. MT: So, when you found your way to writing, what was the first thing you wrote? How long was it before you began writing novels and which novel was the novel that got you an agent? Do you have any advice for aspiring authors about this? BE: I’ve been writing something or other since I was a kid. I used to spend a couple weeks every summer at my grandparents’ house on the Jersey shore. I would bang out short stories about vampires and werewolves on my grandmother’s typewriter. Fortunately, as far as I know those early efforts no longer exits…! Also when I was a kid, I read a biography of Harry Houdini, and in the book a cop was quoted as saying, “It’s fortunate that Houdini never turned to a life a crime, because if he had he would have been difficult to catch and impossible to hold.” I remember thinking how cool it was that this man knew things people weren’t supposed to know, things that gave him special power. And that notion made a big impression, because since then I’ve amassed an unusual library on topics I like to think of as “forbidden knowledge:” methods of unarmed killing, lock picking, breaking and entry, spy stuff, and other things the government wants only a few select individuals to know. And I spent three years in the CIA, I got pretty into a variety of martial arts… And then I moved to Tokyo to train in judo—this was when I was 29. I think all the other stuff must have been building up in my mind like dry tinder, waiting for the spark which life in Tokyo came to provide. Because while I was there commuting to work one morning, a vivid image came to me of two men following another man down Dogenzaka street in Shibuya. I still don’t know where the image came from, but I started thinking about it. Who are these men? Why are they following that other guy? Then answers started to come: They’re assassins. They’re going to kill him. But these answers just let to more questions: Why are they going to kill him? What did he do? Who do they work for? It felt like a story, somehow, so I started writing, and that was the birth of John Rain and my first book, A Clean Kill in Tokyo, originally called Rain Fall.That was the one that got me my first agent, and it was about eight years from initial idea to first sale in part because I had a busy day job, and in part because at first I didn’t really know what I was doing, and revised that first manuscript more times than I’ll ever remember, getting better at the craft as I did so. If there’s any advice to be found in all that, it’s partly about the importance of indulging your passions. I realize in retrospect that what gave birth to that first novel (and the novels that came after) was a lifelong tendency to indulge certain passions of mine: the forbidden knowledge, politics, judo, jazz, and Japan (where I was living when I started writing the first book). Stories don’t get catalyzed by the things that bore you; they quicken instead when you do the things you love. So if you want to write a story, or just avoid writer’s block, I recommend finding a way to do the things that fascinate you, the things you love to do, the things you obsess over and that make the world go away. Those things are like coal being shovelled into the furnace of your imagination, and denying yourself those things is like denying your mind the nutrition it needs to thrive. For more thoughts on how to find the time, discipline, and structure to write a novel (hint: don’t watch television), a TEDx Tokyo talkI once gave is a good resource. Another lesson is, don’t give up. The first fifty responses I got from agents I contacted were all rejections. Most were form letters, but a few had some helpful suggestions scribbled in the margins. A few had some really bad suggestions, one of which I still remember: “Try third person.” That would have been a disaster for A Clean Kill in Tokyo, leaching the story of the appeal of first-hand access to the mind of a ruthlessly competent but conflicted contract killer. I ignored the bad suggestions, considered the good ones, and did an extensive rewrite. Eventually, a friend of a friend who worked at a publishing house suggested that I send the manuscript to a few agents with whom she worked, one of whom was Nat Sobel, who became my first agent. Nat saw promise in the early manuscript but knew it wasn’t ready for prime time; he offered suggestions for improvement that were as extensive as they were excellent, and, about two years later, he judged the manuscript ready to go. At that point (this was autumn, 2001), the deals came fast and furious: first Sony’s Village Books in Japan, then Penguin Putnam in the US, then eight foreign offers, all over the course of about two months, all two-book deals. I quit my day job and have been writing full time ever since—a dream come true. And though things have worked out well, if I could do things over, I would have tried to write more consistently. Spending months or even days away from a manuscript detaches the story from your unconscious. Conversely, working on a story every day lights a fire in your unconscious that becomes self-sustaining, igniting new story points even when you’re not consciously working on the draft. So the on-again, off-again approach drastically inhibits your access to one of your most powerful storytelling assets: your unconscious, what I’ve heard Stephen King call “the boys in the basement.” I would also have read more how-to books. There are some excellent books on craftout there, and while I believe they’re of secondary importance to actually writing and to learning to read like a writer, they can dramatically accelerate your mastery of craft. Anyone who tells you “but you can’t teach art,” by the way, is being glib. Of course art can’t be taught, but teaching art isn’t the point. The point is: all art is based on craft—that is, on a body of techniques that can be taught to and learned by anyone with talent. Art is an expression of something unique to you and indeed, it can’t be taught. But without craft, there is no art, because all art is based on craft. The truism that “art can’t be taught” is an observation so pointless and irrelevant that I wonder how it continues as a meme. Maybe it makes artists feel more special, as though they’ve been chosen for unique dispensation by the magical writing muse. Maybe it comforts talented non-artists by freeing them of responsibility for their failure to study. Either way, it’s silly and misleading and ought to be retired. (On the subject of glib pronouncements inexplicably embraced unimpeded by critical thought: Frank Zappa is supposed to have said, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” I suppose this could be true, if the expressive, descriptive, and overall communication possibilities of dance were identical to those of the written word. Are they?) Anyway, there’s no substitute for practice, true, but for any skill you’re trying to learn—a martial art, a language, a musical instrument, writing—there’s an optimal balance of practice and theory. In retrospect, I realize I would have learned faster if I’d informed my practice with a little more theory, whether how-to books, writer’s groups, conferences, or whatever. One thing you shouldn’t conclude from the fact that it was a friend of a friend who put me in touch with the guy who became my first agent is that in this business it’s critical to know someone. That’s a common misapprehension, born of wishful thinking. What matters is writing a great story. The literary agent’s business model involves reviewing everything that comes in, so eventually I would have gotten to Nat, and his judgment would have been the same. Having someone steer me to him speeded things up for me, but that’s about all. In other words, who you know might get a door opened for you, or get it opened a little sooner than you might have opened it on your own. But what happens on the other side of that door is entirely up to you. Manage your priorities accordingly (translation: Write. The. Book). Another lesson: the truth of the adage, “Good writing is rewriting. Sometimes people are astonished when they learn the first bookI’d started was also my first published. What they don’t realize is that how much rewriting went into that manuscript—for the amount I learned from it, it might as well have been my fifth manuscript, not, technically, my first. You have to be committed taking the time and expending the effort to develop your mastery of the craft—the practice side of the practice/theory balance I mentioned earlier. Okay, just a few more thoughts—on what kept me going during the eight years between the first idea for the A Clean Kill in Tokyomanuscript and the first sale of rights for the novel. That can be a long, lonely stretch: no contract, a busy day job, the distractions of everyday life, and no external reason to believe you have the talent or might have the luck to get published. I think that, in life, there are things you can control and things you can’t (or, to think of the whole thing as a continuum, there are things that are relatively amenable to your influence and things that are relatively unamenable). The things you’re responsible for, and therefore the things that can be the source of legitimate pride or shame, are the ones you can control. If you want to be a writer, the thing you can almost totally control is finishing the book. Finding an agent, getting published…that all takes a certain amount of luck and timing and circumstances (although of course your hard work on what you can control will affect these less controllable factors, too). So my attitude was this: I wanted to be published, but if it didn’t happen, I didn’t want it to be my fault. I wanted to be able to look in the mirror and say, “Okay, you didn’t manage to get published, but you did everything you could to make it happen, you finished the book, so you’ve got nothing to be ashamed of and every reason to feel proud.” That attitude—the fear of one day feeling that if I didn’t make it I might think it was my fault—is what kept me going for many years with no external signs of success. Imagine how it’ll feel if you don’t get published and you know it was your fault—and make sure not to let that happen to you. MT: Can you tell us about Livia Lone? She has her own series and we learn so much about Livia in the first novel. Would you mind telling us about Livia, why she is who she is, and why being Livia Lone played into the greater part of the novel? BE: Well, the book jacket provides a pretty nice primer, I think: Refugee. American. Victim. Survivor. Cop. Killer. When we meet her, Livia is a Seattle PD sex-crimes detective. But as the above primer suggests, she’s much more than just that. Maybe the best way to gain an initial understanding of her character is to recognize that she is fundamentally a sheepdog. The world, a mentor explains to Livia sometime after she has been rescued from traffickers and is intent on finding her missing sister, is made of three kinds of people: sheep, wolves, and sheepdogs. Sheep are ordinary people, obviously, while wolves are predators. Sheepdogs, though—soldiers, police, firefighters—while fanged like wolves, possess an instinct not for predation, but rather for protection. Livia is a born sheepdog. Someone with a deep-seated, hard-wired need to protect—albeit a need tuned by trauma to the level of obsession. Because what happens to a person who is so wired for protection—not just in general, but in particular for the little sister she adores—when as a child her ability to protect is horrifically ripped away from her? That sheepdog might start protecting the flock not just by warding off the wolves. But by hunting down the wolves. And killing them. So on a superficial level, Livia Loneis a story about revenge. But on a deeper, and more important level, the story is about love. MT: Some of the scenes are brutal and are hard to read, and I imagine hard to write. Would you mind telling us what it was like writing Livia’s history and why it was so important to talk about this sort of history, this sort of life, and how do you think Livia’s past makes her the character we read about today? BE: From the beginning, I was at least as interested in the forces that shaped Livia in the past as I was about the present-day plot. Happily, those two timeframes, delineated as “Then” and “Now” chapters in the novel, come together, as the past gradually catches up to the present. Understanding Livia’s past was important to me for several reasons I can articulate. For one, I wanted her to be real. She is capable of extreme behavior—even driven to it—and exceptionally capable tactically. These things are possible, but unlikely, and if I don’t understand the foundation myself, and present it to the reader, then the drive, the capabilities, and the behavior will be just a cartoon. And while there’s nothing wrong with cartoons, I’m more interested in something more realistic. Presenting Livia’s past was also important to me because technically, she’s a murderer—even a serial killer. And if you don’t understand her past, you won’t be able to sympathize with her actions today. Livia is a survivor of some of the worst trauma imaginable. I want people to understand not just that the kind of trauma she experiences actually happens, but that someone can survive it—albeit with damage she still struggles to sublimate and overcome. MT: Were there any novels that inspired Livia Lone or John Rain in their lives or professions? What books do you constantly turn to in your writing both in and outside of the genre, and what are your favorite books in general? BE: The assassins of Trevanian—Nicholai Hel in Shibumi, and Jonathan Hemlock in The Eiger Sanctionand The Loo Sanction—were definitely an influence for Rain. Both were men of superior intellect, refinement, and (paradoxically) morality. In fact, there’s a line in Shibumiabout Hel as a tiger battling a blob of amoebas, and that theme, which was also present in the corporate-controlled world of the original Rollerball(“It’s not a game a man is supposed to grow strong in, Jonathan, you should appreciate that”), resonates for me. Books that inspired Livia…definitely the works of child protector and novelist Andrew Vachss, and the jaw-dropping nonfiction Sex Crimes, Then and Now: My Years on the Front Lines Prosecuting Rapists and Confronting Their Collaborators, by former sex crimes prosecutor Alice Vachss. Also, Dave Grossman’s phenomenal On Killing: The Psychological Costs of Learning to Kill in War and Society, which is where I first came across the sheep, wolves, sheepdogs concept. Books that I turn to in my writing…well, sometimes I’ll warm up with something I’ve written previously, to get my head back in that world. And I read a lot of nonfiction. As I like to say, most of my plots are courtesy of the US government, because what’s bad for America is great for thriller writers. And my favorite books in general…that would be a long answer, so I’ll try to narrow it down by defining “favorite” as the ones I’ve read the most. At the top of that category would be Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, which is both one of the best-told stories I’ve ever come across and an impressive study of human nature, too. And Judy Blume’s Foreveris where I learned to write a good love scene. J MT: Can you tell our readers (as few spoilers as possible, please!) about what and who Livia Lone and John Rain are in relation to this new book—how they have evolved and if this is the first of your books our readers buy, can you give us just enough clues to figure out how to read the book as a standalone? What essentials must the reader know before diving in? BE: All my books are designed to function both as series entries and as standalones, so anyone can appreciate The Killer Collectivewith or without having read any of the previous Rain or Livia books. If I had to compare Rain and Livia…well, they’re both survivors, they’re both killers, they’re both exceptionally methodical. But the differences are probably more significant: Livia was created by trauma, while Rain’s origins lie in an innate attraction to conflict. Livia is motivated by a deep-seated need to protect, while Rain’s motivations are less noble. And Livia is primarily a sheepdog, intent on guarding the sheep, while Rain is much more a wolf, grappling with guilt about having preyed on others. Rain has been around for a while—he was first published in 2002!—and in some ways he’s changed. He’s less the lone wolf he was at the outset. He has a clan now, which creates complications. He’s older, and grappling with an increasing awareness of his own mortality, and with the increased weight of the life he’s led and what he’s done. He’s been trying to retire—to kill his way out of the killing business—but never quite seems to make it. And Livia teamed up with Rain’s partner, former Marine sniper Dox, in the previous book, The Night Trade,and that turned into an interesting relationship. So I started wondering…what would happen if Livia, in the course of her Seattle PD sex-crime detective duties, uncovered something so big that she was targeted in an attempted hit? Would she call on Dox for help? Would Dox call on Rain? And what if Rain had earlier been offered the hit himself…? Once I started playing around with it, the idea became irresistible. The characters from the Rain and Livia universes are all so different—different motivations, different training, different worldviews, different personalities—that the idea of forcing them together, all their tangled histories, and smoldering romantic entanglements and uncertainties and jealousies and doubts, under the relentless pressure of extremely resourceful adversaries…looking back, it seems almost inevitable! And I sure had a lot of fun doing it. MT: When reading the book, everything felt smooth and glorious to me. However I read back over the synopsis and thought this is a lot for a new reader to take in. (Readers: I do encourage you to read this book as well of all Barry’s books, I just want him to break down the story for you!) Would you mind breaking down the synopsis while also avoiding spoilers? BE: Well, it starts like this: THE LONE WOLVES OF BARRY EISLER’S BESTSELLING NOVELS COME TOGETHER IN A KILLER TEAM! And I’d add… When a joint FBI-Seattle Police investigation of an international child pornography ring gets too close to certain powerful people, sex-crimes detective Livia Lone becomes the target of a hit that barely goes awry—a hit that had been offered to John Rain, a retired specialist in “natural causes.” Suspecting the FBI itself was behind the attack, Livia reaches out to former Marine sniper Dox. Together, they assemble an ad hoc group to identify and neutralize the threat. There’s Rain. Rain’s estranged lover, Mossad agent and honeytrap specialist Delilah. And Black op soldiers Ben Treven and Daniel Larison, along with their former commander, SpecOps legend Colonel Scot “Hort” Horton. Moving from Japan to Seattle to DC to Paris, the group fights a series of interlocking conspiracies, each edging closer and closer to the highest levels of the US government. With uncertain loyalties, conflicting agendas, and smoldering romantic entanglements, these operators will have a hard time forming a team. But in a match as uneven as this one, a collective of killers might be even better. That’s the gist… and no spoilers, either. J MT: How do you think you’ve improved as a writer with The Killer Collectiveand what makes your writing different as you grow older, write more books, and learn more about writing and the world in general? BE: First I’d just like to thank you for the flattering assumptions in that question. J I’ll leave it to readers to judge whether I’ve gotten better and all that, but if I have, I think it probably comes down to experience with the craft and experience with life. Anyone who takes a craft seriously is going to get better with practice—it’s part of what makes a craft rewarding and even, well, a craft. And given that I was 29 when I started my first novel and that I’m 54 now, well, that’s a quarter century of time in the saddle—a pretty long stretch in which to learn, consider, reflect, and hopefully to grow. When dreaming up a story, you can only draw on what you know, and you know more when you’re older than you do when you’re young (at least you do if you’re doing it right). Which means if things go well you should have a richer palette to paint from later in life than earlier on. I feel that’s been the case for me. MT: Is there a character you identify with more than others? Do you feel you’ve put certain aspects of yourself in John Rain, Livia Lone, or any of the other characters in your books? BE: Well, writing Dox makes me laugh more than writing any other character (although I was surprised to find that Daniel Larison, my “angel of death” former black-ops badass, was cracking me up in The Killer Collective), and Livia makes me cry more. Which probably means I strongly identify with Dox and Livia, at least in certain ways. I wouldn’t say I deliberately put any of myself in my characters—it’s not as conscious as that. When I get an idea for a character, what I try to do instead is imagine who this person is—what were her formative experiences, what does she think she wants, what does she really want, what is she afraid of, how does she look at the world, what makes her tick. In doing that, of course the raw material is derived from things I recognize in myself, but what I try to do is take that raw material, distill it out, culture it in the medium of this new character, and see how it grows. I think that’s the right approach generally: as Robert McKee says in his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, the inquiry isn’t about you, and it’s not about the character, it’s more what would you do if you were the character. In practical terms, that means there aren’t any characteristics of my characters I don’t recognize in myself (I think that would be impossible, unless there are things about myself I can’t or don’t want to consciously recognize that are bleeding through layers of repression and manifesting themselves in my characters…which now that we’re talking about it, is an interesting idea and I’m going to think more about it). But the way those characteristics manifests is different. I can be cynical at times, for example, but overall I think my nature is optimistic (perhaps foolishly so, but we’re all victims of ourselves). Rain’s cynicism, on the other hand, is much more central to who he is—a driving force, and something he has to grapple with far more than I do mine. MT: The Killer Collectivefeels more epic in scope, in thrills, mysteries, characters, everything. Can you talk about what has led to your writing The Killer Collectiveand if this isn’t your favorite of your own books, what is? BE: Thanks for that. The book feels epic to me, too, in part because the cast of characters is the biggest I’ve ever worked with, and in part because of what all those characters have gone through and what’s led them to this story. Is this one my favorite? Right now it feels that way, but that could be a recency effect. I do think it’s probably the most nonstop story I’ve written—not just the action, but the emotions, too. Managing all these characters, all their differences and distrusts, with one tenuous romance in progress and another one being resuscitated from near-death, all while determined, capable enemies are launching formidable attacks, was technically challenging. Plus the milieus are so different—Livia is a police detective, Rain and the others are assassins and spies. So the initial chapters moved back and forth from a police procedural feel to a spy thriller feel, with those disparate worlds merging as the story progressed. Which was challenging, but I think (if I may say so) it all came in beautifully balanced on the page, with everyone getting key solo moments, one-on-one moments, and, of course, team moments, because, after all, this is a killer collective. MT: Going back to writing in general, what book was the hardest book you’ve ever written? Which book or books gave you the most trouble? Regarding Livia Loneand The Killer Collective, what do you feel was or were the hardest parts you have to deal with when writing your most recent novel? BE: Livia Lonewas hardest because of what I had to put her through in depicting her past. Graveyard of Memorieswas hardest because I had to recreate 1972 Tokyo, which involved a fair amount of research. The Killer Collectivewas hardest because the canvas was so broad. I guess writing books is just hard…? J MT: Can you talk a little about your writing process? What is it like to be an author like yourself? Are you’re a morning, noon, afternoon, evening writer? How many words do you write a day? Where do you write? BE: I’m always happy to talk about my process, but like to note upfront that whatever works for me is only something that by definition can work for someone, and not something that will necessarily work for anyone else. I love that Bruce Lee quote: “Research your own experience. Absorb what is useful, reject what is useless, add what is essentially your own.” So what works for me…I follow a lot of news on geopolitics, the media, and government skullduggery. Not the establishment stuff—that just tells you what you’ve already been indoctrinated with, and the world doesn’t need any additional regurgitation of conventional (and failed) wisdom. I’m talking about Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now!, for example, or Marcy Wheeler at Emptywheel, who covers political stuff with almost psychic insights. Throw a few invented characters into Wheeler’s articles and I swear you’d have a dozen terrifying thrillers. And I think a lot about what I read, and sometimes write about it, too, on my blog The Heart of the Matter. From all that I get plot ideas, many of them direct from the U.S. government—like the mass domestic surveillance program at the heart of my novelThe God’s Eye View. But the plot ideas would be worthless if I weren’t processing everything I read about through a human-nature filter. Plot is one thing, but without that human nature element, I don’t think you’d get a story. And then I take walks and ask myself questions about the who, the where, the what, the why…I dictate the answers, and write them up, and the answers lead to more questions…and at some point, an opening scene comes to me, and I’ll start writing. And then it’s iterative: I write, then I walk and think, and then I write some more, and as the story progresses, the ratio of thinking to writing gradually shifts from almost all thinking and almost no writing to the reverse of that, so that by the time I’m writing the last quarter of the book or so I’m on fire and putting in long stretches of writing—3000, 4000, once even 8000 words in a day. That stretch of unimpeded running toward the end is a beautiful high, and a lot of effort, a lot of foundation building, precedes it. And when I write the words “The End,” which is usually in the wee hours of the morning, I try to do something special to mark the moment. Open a certain whisky, drive out to an overlook and watch the sunrise, take a long walk through nocturnal Tokyo, just feeling alive and so satisfied to be done. Until the edits come in, anyway. JBut that part is easy by comparison. MT: A lot of both young and aspiring writers as well as some accomplished writers ask me about ending. For The Killer Collective,was it hard to write an ending? Has a book and its ending ever had you stumped? What would you suggest to any writer struggling with an ending now? BE: For some aspects of the craft, I feel like I can give useful advice because I’m conscious of what I’m doing. But for others, less so, and writing a satisfying ending is one of the “less so” categories. For me, it’s mostly instinct, and explaining it would be like trying to explain how to make a punchline funny. All I can say is probably 95% of it is how well you did the setup, because without a proper setup, the best-delivered punchline in the world will still fall flat. But with a great setup, a great punchline is almost hard notto deliver. So yeah, maybe that is reasonably good advice, albeit somewhat Yoda-like. It’s like dialogue: usually when dialogue is falling flat, the problem isn’t in the dialogue, it’s in the characters, as in the writer doesn’t know them, doesn’t feel them, well enough. And if the ending isn’t there, it might be because what preceded it wasn’t quite right, meaning you have to fix something more fundamental than you might like. It’s like if the walls of the house you’re building keep collapsing, the problem might be not in the walls, but in the foundation. But that’s a hard thing to acknowledge, because it entails a lot of rebuilding. MT: Do you think you will keep writing about these characters, or will you eventually end the series and write about other people? Do you think even if you write a standalone or something else, all of the people in your writing universe will still be there in one form or another? BE: I’ve never been good at predicting these things—I actually thought at the time that my first Rain book was a standalone!—so I won’t even try. I’ll just say I’ll keep writing whatever comes to me, existing characters and new ones, and hopefully the stories will keep on delighting me and others. MT: The country is currently in a sort of turmoil, and I love asking my favorite authors this question. If you were to give the whole of America one of your books, what would you give to these people and why? What about another author’s book or books, and what would be the reason behind this? BE: Oh, that’s a hard one! Well, I’m fond of my essay, The Ass is a Poor Receptacle for the Head: Why Democrats Suck at Communication and How They Could Improve. But even if any top Democrats decided to read that one, it’s a safe bet they lack the motivation or capacity to absorb any of its lessons. So I guess making a gift of it might be a bit of a waste. That said, I’ve never seen a Democrat with a better instinct for communication than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. She would get the essay. But she’s also the least in need of it! Another author’s books…that’s another hard one. I think the ones that have been most personally valuable to me would include Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends & Influence People, which is incredibly insightful about human nature and describes a disarmingly beautiful approach to engaging with others. Amusing Ourselves To Death: Public Discourse In the Age of Show Business, by Neil Postman, completely changed my understanding of media. Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Fouris, sadly, full of insights into the worst aspects of human nature and was stunningly prescient—proving, as though any further proof were required, that if you understand human nature, you can predict events exceptionally accurately. And a recent one that tapped into all kinds of things I’ve been thinking about, connecting, correcting, and expanding them, is Why Buddhism Is True, by Robert Wright. MT: Do you think you’ve written the novel you’ve always wanted to read but never found yet, or do you think that novel is still coming and in the works? Speaking of next works, can you tell us what your next book will be after The Killer Collective? BE: I’ll let Rain answer that, from A Lonely Resurrection: I took a long, meandering route, moving mostly on foot, watching as the city gradually grew dark around me. There’s something so alive about Tokyo at night, something so imbued with possibilities. Certainly the daytime, with its zigzagging schools of pedestrians and thundering trains and hustle and noise and traffic, is the more upbeat of the city’s melodies. But the city also seems burdened by the quotidian clamor, and almost relieved, every evening, to be able to ease into the twilight and set aside the weight of the day. Night strips away the superfluity and the distractions. You move through Tokyo at night and you feel you’re on the verge of that thing you’ve always longed for. At night, you can hear the city breathe. I feel that way about writing books. Each one is beautiful—a little mystery solved, a deep-seated emotional itch scratched. But it doesn’t solve anything. You feel you’re on the verge, but you never quite get there. But I also find something lovely and satisfying in that. Maybe it’s mono no aware—the sadness of being human. The book I’m working on now is a Livia Lone standalone. MT: There are so many things you can take away from a novel—fun and entertainment, ideas for works of your own, some sort of new understanding of the world around us, learning more about ourselves and the people we know, etc. What is the one thing you want readers to take away from your novels when they’re done? BE: I certainly hope they’ve been entertained, and invested in the characters to the point of laughing and crying and being deeply moved. And if they reflect a bit on what it feels like, what it means, to be on “this crazy ride of life,” as Dox might put it, that would make me happy, too. And if some of them were to read the bibliography, and learn that the government programs and all the other skullduggery I write about isn’t fiction at all, well that’s what the bibliography is there for. So hopefully, the books will educate as well as entertain. MT: This may like a cheesy question, but I actually love asking it and the various questions I get. What do you think the writer’s most important job is? BE: Stephen King says the writer’s job is to tell the truth. I like to say things my own way, but I can’t really improve on that. MT: The Killer Collectiveis a big, wonderful book, so exciting, nail-biting (I mean quite literally), and so amazing to walk away from, even if you walk away wanting more. The book solidifies your standing beside the greatest suspense and thriller writers in the world, and it means so much to me to be able to interview you, to talk about your book and writing. For all of our readers, I really hope you will purchase a copy of this astounding book, The Killer Collective, If you’re not convinced by me, look at Amazon and Audible and see how fast it’s moving up the list of preorders. As for Barry, thank you for the answers to my questions, and please leave any thoughts or comments below. BE: Thanks for the very kind words, Matthew, for the thought-provoking questions, and for enjoying the books! Matthew Turbeville: If it means anything, when typing up my questions I tried to change my front to New York Times Bestselling Author instead of Times New Roman. Amy, how does it feel to be the most coveted new author in all of crime fiction—someone compared to Megan Abbott, Laura Lippman, Tana French—the greats. What do you feel is the biggest leap and struggle between switching from groundbreaking debut to blockbuster follow-up? (Plus a book about Tori Amos in between!)

Amy Gentry:If anyone considers me in the company of any of those three authors, I’m insanely honored! They’re three of my favorites, and in many ways, my role models. Moving from the first to the second book is always a challenge. You spend years crafting your debut, because it has to be absolutely perfect before you can sell it. And since you don’t know whether anyone will ever read it, it’s written one hundred percent for you. My second novel LAST WOMAN STANDING was written under contract, which means I had to figure it out a lot faster--none of the long detours and rambling pre-writing sessions and trying out three different settings that I did for Good as Gone. I was also pregnant when I wrote LAST WOMAN STANDING, desperate to finish before the baby. I had a timeline all written out, but in my panic I wound writing a completely bizarre alternate ending, and still not finishing it. I remember sitting in the hospital with the pitocin drip going, emailing my agent on my phone. It was all very bizarre. I had finished the ending with a newborn crying in the next room. Obviously there was an extension involved. . .! My editors at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt were extremely patient and helpful through it all. But it certainly wasn’t the leisurely part-time writing experience of Good as Gone. The Tori Amos book, which had been under contract since before I had a literary agent, was a further wrinkle. Anyone working on two books at once will tell you that no matter how hard you try, both rounds of edits always end up hitting your in-box the same day. MT: When you first published Good As Gone, people were obsessed. We met because I was obsessed and wouldn’t stop tagging you on Facebook (I still don’t but we don’t want the authorities to know that!)—what inspired this novel? You were famous, if I remember correctly, from being the brilliant debut author who didn’t meanto write crime fiction. Can you explain to us how that happened to? AG: I didn’t read a whole lot of crime fiction--or at least, I didn’t think of myself as reading it, although I had read Lippman, Megan Abbott, Ruth Rendell, Barbara Vine, Chandler, Hammett, and the great Patricia Highsmith. But somehow, even though I had read many of them in grad school, I didn’t think of myself as knowing a lot about them. I always wanted to write like Henry James--not in his style, obviously, but stories of incredibly twisted people messing with each other’s heads, and trying to be good people and failing miserably. That’s what I thought I was writing with Good as Gone--a twisted family melodrama wherein the mother suspects her daughter is an impostor, and we have to figure out which one of these two women is seriously screwed up. (I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say: both of them!) Anyway, there was a kidnapped girl sitting right in the middle of the book. I felt like kind of a dummy when I realized it was obviously a thriller. Once I began thinking of it that way, the whole thing fell into place. And I looked at my bookshelf and suddenly it made sense that I owned twenty-three books by Patricia Highsmith. Almost all the stories I want to tell involve psychological suspense, even if they don’t have dead bodies in them. And lots of them have dead bodies! MT: Attica Locke semi-recently said that all fiction is crime fiction. Do you agree with that? What do you feel is the single greatest crime committed inGood As Gone? That may be a really loaded question/answer so feel free to elaborate on that. But also the concept of the kidnapped girl and returned woman—sure, I’m sure it’s been done before, but you made it feel so new. How did you decide to approach the issue and how did you come about your completely unique approach? AG: I agree completely that all fiction is crime fiction. Henry James is crime fiction, but instead of murdering each other quickly, they murder each other slowly, over hundreds and hundreds of pages. In Good as Gone, everyone (except possibly Jane, the little sister) has committed crimes of desperation by the end of the novel. The kidnapping is the biggest crime depicted in the novel, but the book is far more concerned with the longer-lasting violence of retraumatization, the way our harmful ways of thinking about sexual violence victimize the same vulnerable people over and over again. That’s why the structure of the book includes a backward chronology, diving into the past of the woman who calls herself Julie. Trauma rearranges time, it rearranges identity. The whole family has reordered themselves around it, and that, too, is a kind of violence. MT: Before you stumbled upon crime fiction, who were your favorite authors? Now that you have found what I hope you feel is your true calling (I love your books so much I couldn’t live without them!) who are your favorite crime writers? AG: Before my life of crime, I went through phases with James, Highsmith, Dostoevsky, Shirley Jackson, James Baldwin, Muriel Spark, Kate Atkinson, Kelly Link, Tessa Hadley, Jennifer Egan, and various others. In terms of crime novelists, the three writers you listed above--Abbott, Lippman, French!--are a holy trinity for me. Every new French book that comes out, I have to take several days off to celebrate. I’m also a huge fan of Sara Gran, whom I discovered relatively recently. I love short books that leave you completely gobsmacked and hers are so short but they feel like universes unto themselves. MT: Megan Abbott loves your new book, and so do a whole lot of other people. Last Girl Standing is part Strangers on a Train, part Single White Female, part Steph Cha (I love her so much). My first question is an obvious one: why in this time period, with Trump, a wall, anti-Semitism, do you make your protagonist half Hispanic, half Jewish? I’m sure there are multiple layers of why the protagonist is who she is, and I’d love to hear about them. AG: Yeah that’s a big question. One big thing is that I got called out on the Alex Mercado character from my first book, the P.I. character, not having a bigger role. Someone I quite respect said that he was one of the best, most likable characters in the book (agreed!) and wished he could have had a bigger role, suggested that it was disappointing that this Latino character didn’t turn out to be central to the story. I have often thought about using Mercado in future books, but I knew I would be writing female protagonists for the foreseeable future, and that question of whether they always had to be white, even though I live in Texas and my books were set in Texas where whiteness is far from the norm, nagged at me. Once I realized it was a book about a stand-up comic from Amarillo, I just felt that her character made sense as a non-Spanish-speaking Latina with a mixed ethnic identity, who struggles with feeling that she doesn’t fit in with either the mainstream comedy scene (read: white dudes) or the Latinx comedy scene in Austin--because she does’t speak Spanish and she’s not a dude. Dana is always stuck between two places (Austin/L.A.), two ways of seeing the world, two ways of coping with trauma. It’s a very binaristic book in that way. And it made sense that she would be biracial. Moreover, to talk about how women are marginalized in comedy in 2018 without some look, however compromised by my own subject position as a white woman, at the marginalization of non-white women in those fields--that just didn’t make sense to me. As for how our current political climate factors into that--it’s hard for me to put into words, so I’ll quote Tori Amos: “Girl, you have to know these days which side you’re on.” It’s very much a book about choosing sides, even when that’s impossible. MT: What book or books, and what movies, what TV shows inspired this book? One movie that comes to me is Heathers, except Christian Slater is a beautiful woman. AG: Ha! That’s a point of reference I wouldn’t have thought of at the time but it’s very good. Of course LAST WOMAN STANDING is a straight-up, unabashed Patricia Highsmith rip-off--ahem I mean homage, with the doppelganger character from Strangers on a Trainappearing out of nowhere to represent and express all the repressed fury of the protagonist. But we saw what happened when I tried to do a Henry James homage, so no doubt my Highsmith homage turned out similarly warped. MT: I’m assuming this novel was written at least a year of two ago—while when hatred was high, it wasn’t nearly as public and unashamed as it is now. Hatred is everywhere, and it seems you pick this racial and sexual hatred and bring it to the forefront. So, I’m wondering if you think of writers (including yourself) as sort of foreseers, people who can predict social climates, how things will be by the time they finish and publish their novels. It really feels like you’re a blind woman warning everyone about an upcoming war—which reminds me, Madeline Miller needs to write more too. AG: The hatred you’re talking about--I think it’s very pragmatic. If you stay in your place, they will love you. When you don’t accept your position, the love turns to hatred instantly. A lot of women are writing about rage right now because we have all collectively decided not to accept this version of reality. But rage doesn’t feel good. Rage is a beautiful, terrible, righteous infection. It’s a last-resort response to an undeniable truth. The question is, how can we harness it without getting eaten alive by it? In this book I am trying like hell to answer that question, and I can’t. I just can’t. The answer for me, and I think for a lot of writers, was to channel the rage into writing a book. Not very helpful, but if what you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. So I don’t think we’re seers--I think we just have the ability to get things into words that everyone else is thinking and, more importantly, feeling. Activists are out there yelling at people in restaurants. That’s probably more useful work than novel-writing. MT: You are an English PhD, you review books, etc, so it seems obvious you would become a novelist eventually. Would you mind explaining your own adventure into writing novels, and would you ever write a story collection, crime or no (I would buy it!). AG: I have written novels since I was a little kid, though I never finished one until senior year of college. After that, I thought I would become a novelist right away. I almost finished one, but I abandoned it at the critical two-thirds point. (That last act is still the hardest to write!) I was broke and I had to move back home. My mistake was in thinking that because I couldn’t figure out how to write a novel immediately while waiting tables in a strange new city, I needed to abandon it entirely for ten years. I went to grad school and started reviewing books because I did not know that being an author was actually a real profession where you could make money, and these other things seemed like more practical avenues for my talents. (They weren’t!) It was only when I had failed miserably at everything else, and was contemplating every passing whim for a possible profession--cake-decorating was on the list--that I started writing Good as Gone. I read all these corny self-help creativity books like The Artist’s Wayand The War of Art. And my husband, who was making payments on my student loans at the time, kind of talked me into it. I owe him a huge debt of gratitude for many things, but chief among them, he hooked me up with the woman who started my writing group. And that writing group is how the novel got written. I have written only a handful of short stories in my life, and none of them are very good. I’d like to develop the skill someday, but I have a lot of novels to get through first. MT: So, there are only so many things about Texas I love: you, Larry McMurtry, Jeff Abbott, this one vegan eatery called Bok Choy located in the hellmouth aka San Antonio, my wonderful and very favorite friend Melissa (please meet her during your tour in Houston!), Beyoncce and Solange and Tina, and there are a few more but I’m mostly forgetting. It’s one reason why I wonder why Dana, the protagonist of Last Woman Standing, would return home. The comedy scene is smaller, it seems, so maybe she has a chance. And maybe she gets a chance. I’m trying to be spoiler free but would you mind filling us in on just as much as you’d like readers to know on your delicious all-you-can-eat-butffet follow-up novel Last Woman Stnading? AG: I love Texas, although it has been somewhat trying to live here as an adult woman who wants to have reproductive freedom. Growing up in Houston, I always thought I would get as far as I could, and I lived in Portland and Chicago and each time wound up coming back here. Austin, as Dana says in my book, is the Velvet Coffin. So incredibly comfortable. But there’s something about Texas, too, that’s very friendly and very open. It’s not just Austin that’s weird; Texas, too, is a very weird place. But I digress. The reason Dana comes back to Austin is the same reason I came back to Austin twice: she feels she’s failed. Something happened to her in L.A., and it scared and shamed her, and she came home with her tail between her legs. Austin was home base. I’ve known so many performers who did stints in New York, L.A., and Chicago, and then came back home when the money ran out or the winter got too cold. Performing is such an intense career. You actually use your body to make your art. And you start feeling used up. Dana likes Austin a lot less than I do--she’s in a very challenging corner of it, in the stand-up world. But even the stand-up scene here is friendlier than in a lot of places. In a small pond, there’s a lot more collaboration. People don’t feel as threatened by eachother. And one of the things that’s happened in LAST WOMAN STANDING is that Dana left Austin right when the scene blew up, so it actually got bigger and more threatening while she was in L.A. She comes back, and it’s too competitive to feel comfortable, but still not a place where you can find creative jobs that pay. That’s a story I know all too well from performer friends. MT: In college, my best friend Melanie said once that when she gets rich or marries rich she would like to form a vigilante squad of people who kill rapists. In a way, in the novel’s beginning, Last Woman Standingis somewhat about revenge against men, things that start small but escalate quickly. I don’t want to make you angry (I get angry when I think about this subject) so I won’t ask you what you think men who abuse women in any way should have to suffer through, but I will ask is if you agree with anything Dana and her new friend do? AG: It’s one hundred percent wish fulfillment. I have revenge fantasies all the time. How can you not? If you’re sure--and, based on personal experience as well as volunteer work with survivors, I am sure--that nothing will happen to these people, that there will be no consequences for their crimes, how can you not want to get revenge? In writing the book I wasn’t interested in what the men deserved so much as what the women deserved. I felt that Dana and Amanda deserved their rage, their horror at what had happened to them. They deserved to have it acknowledged, that what happened to them was wrong. They deserved for there to be consequences. MT: So as you know, and as I will tell our readers, I was blind from a botched surgery two months under a year since I had it and received my copy of Last Girl Standing. It performs miracles, people. I can see now! But other than that, it’s an amazing novel. Beyond amazing. What were your fears when writing a sophomore novel? And—I would like to stress this—this is not Good As Gone 2. This novel is something completely new and innovative, the voice as noir as Patricia Cornwell and as compelling as Megan Abbott. The dynamics of the relationships are reminders of Laura Lippman and the surprises and twists are as well executed as Alison Gaylin. But really, it’s all Amy Gentry. So how did you make such a unique sophomore novel? AG: I cannot take credit for making a blind man see, but I’m so glad it helped in any way! In terms of writing a unique sophomore novel--time pressure had a lot to do with it. That sounds blasé, but actually it’s kind of a blessing to be forced to pick your first good idea and run with it. To work on this faster time-scale--and remember I was writing a nonfiction book at the same time, and by the way I actually I drafted a completely different novel, too, that I wanted to get out of my head but that wasn’t suitable for this contract--I had to summon everything I had learned in Good as Goneand boil it down to its essence. I scrapped fancy structures and alternative POVs and just concentrated on telling the story that scared me most--the story of a woman who lets go and becomes pure rage. The one thing that helped me, structurally, was to develop the theme of doubles and doppelgangers throughout the book--not just Dana/Amanda, but also Dana and Betty, her stage alter-ego. There are a bunch more doubles throughout the book, but I would get into spoiler territory very quickly if I went there. That theme of mirroring made me want to use a 4-act structure, which is basically the same as a 3-act structure but it has a really strong central hinge that divides the book neatly in two. Once I figured that out, the book got easier to shape. It’s very much about passing through the looking-glass, seeing what life is like on the other side, once you’ve accepted that you live in a much darker world than you wanted to admit. MT: I have to say, I’m so relieved that you, one of my favorite authors, did not succumb to the sophomore slump. Still, it’s hard to compare your two novels—they’re so different in every way possible. An interesting question that I’ve been juggling about in my mind (I’m not a good juggler) is how Megan Abbott, and many others, have become the leading writers and readers of crime fiction. What does it mean that women are now in control of the most violent, most destructive, but also most nuanced and interesting genre in literature? AG: I think (and I bet Sarah Weinman would back me up on this) that they always have been. Big props to Gillian Flynn for reminding the world, with Gone Girl, that the domestic has always been the pulsing heart of noir. Go back and watch The Reckless Moment, directed by Max Ophuls in 1949. Watch Joan Bennett hide that body so that she can preserve the fiction of happy domesticity in a post-WWII world that just doesn’t make sense. God it’s so good! We’re in a world that doesn’t make sense right now, and we’re being told to pretend everything is normal and it just fucking isn’t. I think women have never had the luxury of ignoring the ugly truths that connect the personal to the political, and in this moment, our insights and our rage are very useful. MT: There’s this idea of repressed memory, of forgiveness but by the end of the novel you’re not sure who you’re forgiving. It’s like the perpetrator—of many crimes against many different women—is wearing a mask. In the same way, Dana wears a mask when she takes on a role completely outside of herself while wearing a wig, a sexy blonde psychopath. Can you talk about the wig, the character she portrays, and without too many spoilers what this means? AG: Many early readers have told me that Betty, the “sexy blonde psychopath” that Dana turns into when she puts this very trashy wig on, is their favorite character. (All I have to say is, you’re all very twisted.) Masks are very paradoxical, because they hide your face of course, but they also uncover or free forbidden parts of you. Think of all the trolling and abuse that came to the surface when people got to use avatars online. It’s not always evil, of course--theater people know that putting on a mustache or a costume of any kind can suddenly put you into a role in a way you could never quite be otherwise. Betty comes along at a time when Dana’s comedy feels very stale and rote to her, and unleashes this whole different side of herself she’s been repressing. Amanda starts that action going, of course, but it’s the Betty wig that tips the scales. True story: the idea for using a wig came from one of my fellow waitresses at a long-ago restaurant job. She was very into vintage, which is already kind of a costume. One day she came to work with a haircut she didn’t like. To cover it, she wore a wig for about six weeks while it grew out. During those six weeks she developed a whole alternate personality named “Denise.” Denise was a nasty, bitchy waitress, and I enjoyed her thoroughly. But eventually my friend was really grateful to retire Denise. She thought she might have a hard time coming back to herself if she kept Denise in the picture much longer. Denise was just too much fun, and she was taking over. How could a novelist not file that away for later? MT: What’s the best book you have read in a long time? On a similar note, and piggybacking on the Toni Morrison quote, do you feel you have written the book you’ve always wanted to read but have never been able to find? If not, can you give us a glimpse into what book that might be and when, if you decide to, you might be writing it? AG: The Witch Elm by Tana French and Claire deWitt and the Bohemian Highwayby Sara Gran are two books that made me gasp--and cry--and feel really jealous. When I read both of them, I thought, “No fair! I didn’t know you could do that!” And although I talk about Highsmith all the time, I really wanted the tone of LAST WOMAN STANDING to be more like a Muriel Spark book--witty and nasty and weird. I don’t think I have succeeded, but I’ll keep trying. An excellent book is often a distortion of the author’s intentions rather than its perfect fulfillment. I hold onto that. MT: Amy, I am so lucky to know you and have you as a friend. I know our readers are so glad to hear from you and get to peek directly inside your mind. You’re a genius. You know that. Feel free to leave any thoughts or anything below, and know how very much we love you and your work, and you’re welcome at Writers Tell All anytime. Thank you again, and I look forward to being haunted and thrilled by your next novel. AG: I certainly do notknow that I’m a genius! But I feel lucky to have you telling me that I am. You’re so wonderfully supportive to the community, Matthew, and we’re all lucky to have you. Thanks for everything you do. Matthew Turbeville: Hi Jessica! I am very thrilled to talk with you. Freefallis a remarkable novel that somehow mixes James Patterson’s short, heart-thumping chapters with the grace of Jeff Abbott and sometimes the ever brilliant and impeccable Alison Gaylin. Before I really dig in here, what brought you to writing? How long did it take to write this novel and were you ever stumped by it? From what I have read this is your first novel (correct me if I’m wrong) and it’s really one of the most remarkable first novels for a suspense/mystery writer. What was it like writing from two (and sometimes three) points of view?