READERS TELL ALL.

|

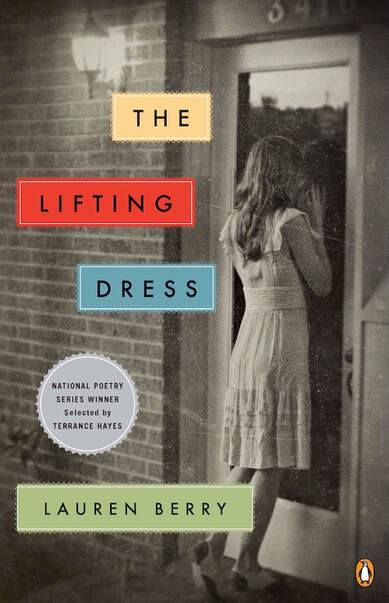

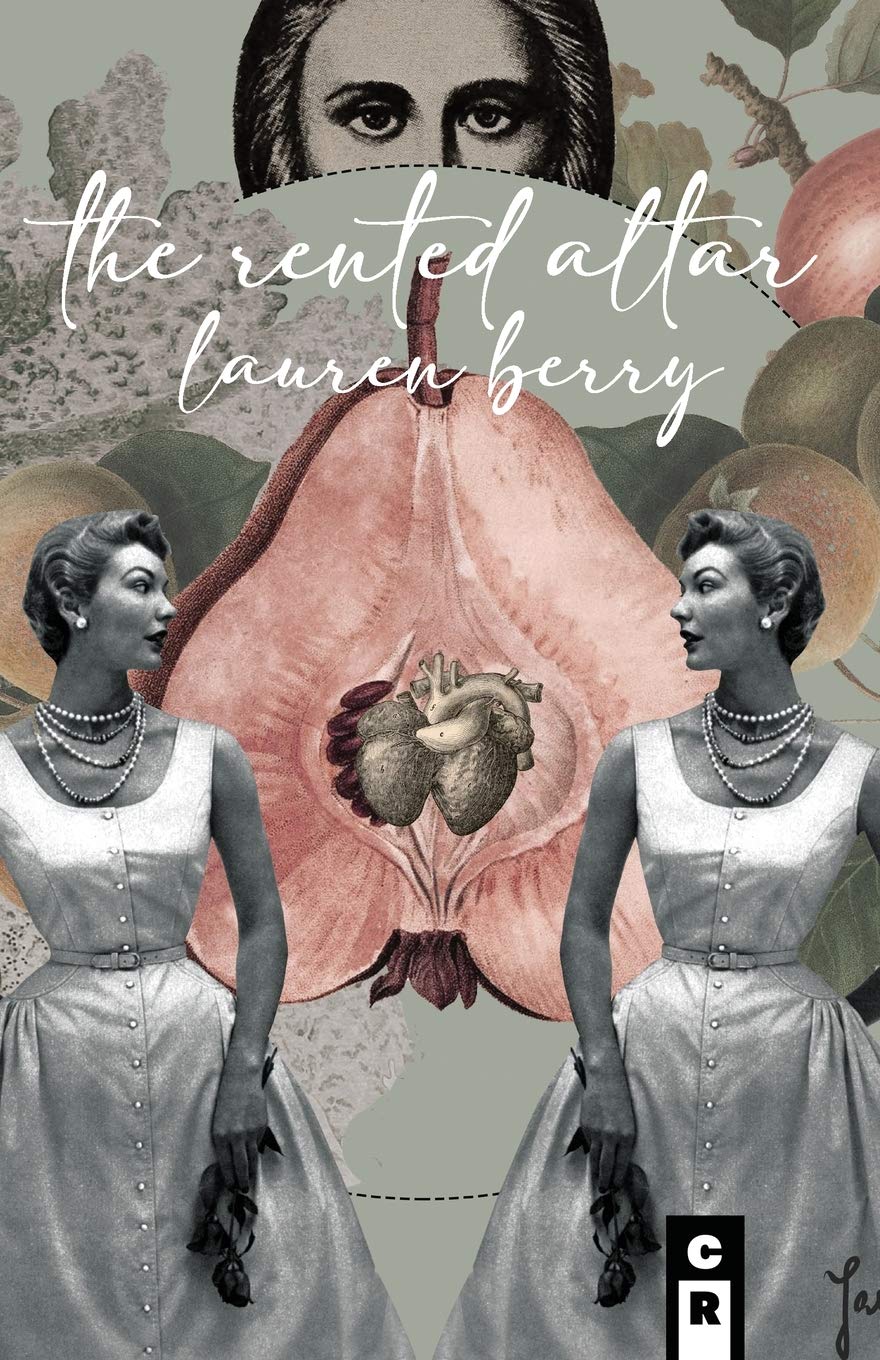

Below, see extensive and essential reviews of Lauren Berry's two collections of poetry, The Lifting Dress and The Rented Altar . Lauren is the winner of the National Poetry Series (2011) and the C & R Press Poetry Award (2020). I hope to also have Lauren on for an interview, so stay tuned! And purchase both of her books for yourself and everyone you know immediately! Pictured above: Poet Lauren Berry; Collections The Lifted Dress and The Rented Altar Below, see extensive and essential reviews of Lauren Berry's two collections of poetry, The Lifting Dress and The Rented Altar

The first time I read the lines in Lauren Berry’s first collection, The Lifting Dress “I should never have been allowed / to be more than a child,” I did the closest thing to crying I’m used to. I got Chinese food, my chest seized up a bit and I had a panic attack or four, and I stood and looked at the mirror in my en suite bathroom wondering, When do I stop growing, and when do I actually grow into the person I want to be, or am supposed to be? I still haven’t answered that question, nor found the answer or provided it for myself, and I still haven’t gotten over the luminous and impeccably talented poet Lauren Berry. The story of the poem collection concerns a young woman’s rape and coping with the aftermath of trauma, which in a way is a universal language, all trauma different, all varying in degrees and severities, but especially open to and directly targeting those more vulnerable, those minorities, those silenced. Poetry is a way of speaking victims learn when they must gush before being interrupted, and this book is like a series of demands and begging not to be interrupted once again. In her first collection, The Lifting Dress, read and really devoured entirely again, again just days after an ER trip, a direct result from my own sexual assault. Some lines were too familiar, like “...she said she lived / because she never / mistook the lighted rooms / of the hospital / for Heaven.” These lines, both referring to childhood and hospital lights are from the same poem, believe it or not. The idea that we grasp on to things, even the intangible handlebars we want to believe are there, that we make manifest for ourselves in our own seeing, are things so powerful they can get us through a lifetime that is really only the brief moments after a trauma, the seconds we survive. These lines come from the same poem, “Big Sister Drinks in the Field Behind the Children’s Hospital,” written years ago now. I imagine any poet or aspiring poet might be frightened by such a young writer who could summon in brief what novelists and story writers like Dorothy Allison and Sandra Cisneros spend careers pondering. Not to throw disparage either writer. I love them both as well (and I do hope Lauren notes mentioning the Cisneros’s wondrous scent, and me likely frightening her nearly to death by slamming on brakes because, frankly, I’d sell my best friend’s soul to meet Cisneros). I’ve yet to even engage with her most recent collection, the ingeniously titled The Rented Altar, but can you blame me with poems, less a punch to the gut than straight through your chest? Gems like “magnolia flower withers” sounds less Steel Magnolias than the more innovative and emotionally obliterating Terms of Endearment, with prejudice regarding my love for the late Larry McMurtry. Descriptions that read “his mother’s quick womb” to make William Gay quiver. Titles alone like “The Year My Father Mistook the Ocean for a Mistress” could be ripped right out of Cane. Flowers play just as much a role in this collection as anything bled (I think leeches, I think ancient and false cures for illness, I think of kissing the first boy I knew in that way, twelve, sitting at the top of a magnolia tree and toppling and falling and scraping my knee). There’s a beauty in the blood, the freshness there, but also the way bugs come, the swamp ferocious, the beauty in blood and in flowers, and the demand that some things which are naturally beautiful always remain this way, when they cannot. I cannot speak enough of this collection. And I feel I cannot provide too many quotes, or summarize too many poems, soliloquys sometimes almost in the way Cisneros writes of the same subject in The House on Mango Street. High praise. It’s amazing how like Zora Neale Hurston, Karen Russell, Lauren Groff, among others, Berry can find beauty (even when tainted, bruised, poisoned) in the same water that fuels brilliant but disturbing Carl Hiaasen novels and meth alligators. Oh, I’m talking about Florida. Lauren Berry’s second stunning collection is the gloriously crafted and C&R Press Poetry Award Winner, The Rented Altar. The poet challenges all other poets working today with a collection about a woman trying to fit into the shoes of her husband’s first wife. I think of my nephew, Rabbit, and changing my first diaper during my first fourteen-hour shift with just us two. He was on antibiotics, I wore what amounted to a makeshift hazmat suit, and how it became more experiment than experience (“experiment” being a word my sister will love to hear). Berry has a gift for twisting births, and rebirths, the pain and labor, the mental and the physical, all of these things into one. One reason I likely won’t ever marry is because I cannot marry a man after he leaves his initial wife upon coming out of the closet. The other is the idea of portraits, paintings, pictures of our new family together. In “Family Portrait with my Stepson’s Heel Against My Stomach,” Berry writes, “Your heart was the only knot. / A labor pain. I sang, Build / a teepee, come inside, / close it tight so we can hide.” The heart, a knot, something worth throwing shoelaces and yarn away, something we learn as boy scouts in case we ever do decide to attempt a personal sequel to 127 Hours. In theory, these can be undone. Practically, easily, quickly, they’re near impossible to untangle. Similarly, the children’s rhyme about a teepee is something I’d never heard until reading Berry’s collection. Here the narrator exists, teaching the child to tie a tighter knot, perhaps trapping the child, perhaps creating her own solitary. Preschool teachers taught me of teepees being unique ways to trap warmth, to survive, and here there is survival, but the reader could see the teepee, the knot, the heart helplessly, endlessly unmanageable, something that can never be made available to the reader or the second wife. Before this, Berry tackles the subject so many of us have dealt with in one form or another, unless you’re the kind of guest that feels OK overstaying your welcome. In one of the opening poems (“The Bar of Dove Soap Hist First Wife Left Behind”) there’s shudder of owning someone else’s property, or possibly not knowing if the property is yours to even touch (“My husband’s first wife / held you to her fluttering, / broken heart.”). And something as simple as a bar of Dove soap, which often is plain, white, scentless, and yet so full of everything the narrator fears, regrets, and if I go deep into abject theory, and I’ll spare you, repulses the narrator at times when this bar which could almost be a blank space does, in fact, dominate everything. There are flowers, there are scents, there are baths throughout the collection which really dominate the book in the need to be a blank slate. The author wants to be something new, and possibly something that can be molded and made or shaped. “She wanted to make things / struggle into beauty. / Was I not enough?” Berry writes in “Red Geraniums,” writing about her mother’s own flowers and that might be her own. To the northern reader, flowers are often a symbol, the blooming sensation of life, but in the South, and in Florida, the weather is often always warm, the flowers not always in peak condition but often always there in some form, and these reminders cannot be uprooted, unless we rip them straight out of the soil, and then there is earth, resembling cracked desert wasteland but more wet from the humidity. Berry takes metaphors than can become cliché and instead uses flowers in a Floridian sense—they are not reborn but always there, and no matter what she does they are the same flowers, the same petals, nothing to separate herself from the woman who came before her, nothing to water and call her own. Berry is an author of rare talent. Her poetry is a shipwreck in the Bermuda triangle, an urban legend so terrifying it’s beautiful. Buy her books now and read her work slowly. Embrace her confidence, even as she speaks through a character or herself, her writing reminding me of one of my closest mentors and favorite friends, the genius poet Julianna Baggott, whose poem concerning Mary Todd Lincoln still swallows me whole sometime. Berry likewise is the same type of all encompassing, entirely consuming heatwave, relentless, a Paul Thomas Anderson movie post-There Will Be Blood, the terrifying and subtle heartbreak in Forster’s A Passage to India, the diving into the wreck, and Berry would make Rich proud. Buy her books now, here and here, and listed plainly below. The Lifting Dress The Rented Altar

1 Comment

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

December 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed